- RESEARCH

- Open access

- Published:

Emotion in lexicon and grammar: lexical-constructional interface of Mandarin emotional predicates

Lingua Sinica volume 2, Article number: 4 (2016)

Abstract

The unique behaviors of emotional (or psychological) predicates have long been studied as a central issue in developing theoretical accounts for the interaction of lexical semantics and argument realization (cf. Talmy, Grammatical categories and the lexicon, 1985; Talmy, Typology and process in concept structuring, 2000; Croft, Surface subject choice of mental verbs, 1986; Dowty, Language 67: 547–619, 1991; Jackendoff, Semantic structures, 1991; Jackendoff, Language, consciousness, culture: essays on mental structure, 2007; Van Voorst, Linguistics and Philosophy 15: 65–92, 1992; Levin, English verb classes and alternations: a preliminary investigation, 1993; Pesetsky, Zero syntax, 1995. etc.). As a preliminary attempt to integrate seemingly diverse proposals, this paper aims to explore the possible range of conceptualizing and hence lexicalizing emotion-related states and activities, by examining the intriguing interactions between lexical and constructional form-meaning mapping relations realized in Mandarin emotional predicates. While it is commonly recognized that emotional predicates differ in selecting an Experiencer or a Stimulus as subject, a tripartite distinction is attested with Mandarin emotional predicates as they display three unique patterns in terms of subject selection, morphological makeup and constructional association. The range of lexical-to-constructional variations in Mandarin lead to the postulation of a distinct causative relation—Affector to Affectee, reminiscent of the notion Effector proposed in Van Valin and Wilkins (Van Valin and Wilkins, Grammatical constructions: their form and meaning, 1996). Three major lexicalization patterns can thus be identified for the emotion lexicon: Experiencer-as-subject, Stimulus-as-subject, and Affector-as-subject. The three lexicalization patterns highlight three distinct ways of conceptualizing emotions. Finally, the isomorphic relation between lexical and constructional patterns in Mandarin is further discussed with its theoretical implications.

1 Background

Emotion is essential to human experience and constitutes an important semantic domain in the lexicon. From the perspective of cognitive semantics, the way an event or state is conceptualized affects the way it is expressed in a language. There are systematic lexical and constructional patterns that associate meanings with overt linguistic forms. Given the non-physical, non-tangible nature of emotions, it is quite revealing to see how emotions are conceptualized and encoded in the lexicon of a given language. As Langacker (1999) asserts, experiences of emotions may be included as conceptual archetypes that provide the cognitive foundation for linking basic grammatical constructs with semantic characterization. In general, emotions are viewed as forces and emotional experiences are treated as causal-evaluative events (Lyons 1980; Lakoff and Kövecses 1987; Talmy 1988; Radden 1998; Kövecses 1998, 2000, etc.). Linguistic evidences also show that conventionalized expressions of emotion are highly metaphorical and metonymic in nature, pertaining to embodied experiences of physiological reactions (Lakoff 1987; Ye 2002; Yu 2002; Kövecses 1999, 2000, etc.). At the lexical level, languages may vary in choosing to lexicalize different facets of emotion and highlight different participant roles as most essential in meaning. As Wierzbicka (1992) observes, emotion terms are semantically diverse and cannot be neatly matched with concepts in other languages or cultures. This study takes on the task of exploring the conceptualization and lexicalization of emotional states/events in the Mandarin verbal lexicon and looks further into the possible range of typological variations in lexicalization patterns of emotion. As lexical semantics plays an increasingly significant role in linguistic research, the study of emotional predicates provides the key to exploring the interaction between syntax and semantics, lexicon and construction, and ultimately advances our understanding of the nature of “semantic-to-surface association” (Talmy 2000: 21), which is believed to be the essential challenge in exploring the cognitive basis of grammar.

Emotional predicates (hereafter EPs), also termed as mental verbs (Croft 1986), verbs of psychological state or psych-verbs (Levin 1993; Jackendoff 1990), psychological predicates (Postal 1970; Filip 1996; Jackendoff 2007), or verbs of affect (Talmy 2000), refer to the class of lemmas that encode a state or an event involving an internal, affective experience. In the literature, there is a wealth of studies investigating this class of verbs since they pose interesting problems for argument structure assignment and semantics-to-syntax mapping theories (Jackendoff 1990, 2007; Levin 1993; Zaenen 1993; Van Voorst 1992; Dowty 1988, 1991; Van Valin 1990, 2005; Pesetsky 1987, 1995; Kiparsky 1987; Croft 1986, etc.). Under the different theoretical accounts lies a more fundamental issue, i.e., in what ways emotional experiences are conceptualized and lexicalized and to what extent languages may vary in distinguishing and categorizing emotional affects. To address the concerns, the present study will explore the semantic distinctions lexicalized in Mandarin EPs and identify the ranges of form-meaning associations peculiar to the lexical subclasses, as compared to those in English and other languages. It ultimately probes into the conceptual bases underlying the lexicalization patterns characteristic of the Mandarin emotion lexicon.

1.1 The issues

As suggested previously in the literature, Stimulus and Experiencer are the two major roles involved in emotion predication (Talmy 1985, 2000; Dowty 1991; Levin 1993; Jackendoff 1991, 2007, etc.). An EP may lexically encode the state of a human Experiencer or the attribute of an external Stimulus, giving rise to the traditional dichotomy of two subclasses, Experiencer-as-subject (e.g., fear/like) vs. Stimulus-as-subject (e.g., frighten/please), as illustrated in Talmy (2000:98):

-

(1) a.

Stimulus as subject: That frightens me.

-

b.

Experiencer as subject: I fear that.

Besides the contrast in subject roles, there are other morpho-syntactic and semantic contrasts in English that need to be further examined (cf. Levin 1993; Pesetsky 1995; Jackendoff 1991, 2007), such as the contrast between an adjectival and verbal predicateFootnote 1, as in 2; the contrast between a transitive and intransitive verbal predicateFootnote 2, as in 3; the contrast between an adjectival passive and a verbal passive, as in 4:

-

(2)

Verbal vs. adjectival predicate

-

a.

Experiencer-as-subject

I envy him.

I am envious of him.

-

b.

Stimulus-as-subject

This excites me.

This is exciting to me.

-

a.

-

(3)

Transitive vs. Intransitive predicate

-

a.

Experiencer-as-subject

I like this.

I delight in this.

-

b.

Stimulus-as-subject

This attracts me.

This appeals to me.

-

a.

-

(4)

Adjectival vs. verbal passive (with by-PP)

-

a.

I am frightened with that.

-

b.

I am frightened by that.

-

a.

The contrast between adjectival and verbal passives is closely related to the important semantic distinction in volitionality and eventivity, repeatedly discussed in previous works (cf. Grimshaw 1990; Dowty 1991; Jackendoff 1991, 2007; Pesetsky 1995; Levin 1993, etc.). While Experiencer-subject predicates in English are mostly stative, Stimulus-subject predicates may be stative or eventive (“inchoative” in Dowty (1991)’s terms), as illustrated in 5 below, taken from Jackendoff (1991:140):

-

(5)

Stative vs. eventive predication in English:

-

a.

Thunder frightens Bill. (stative, non-volitional)

-

b.

Harry (deliberately) frightened Bill. (eventive, volitional)

-

a.

The eventive predication will normally correspond to the verbal passive (with by-PP), indicating a semantic distinction from the adjectival passive. While some of these issues have been dealt with in previous works, few studies have given a comprehensive analysis of the full range of grammatical distinctions in the emotional lexicon.

1.2 The scope and goal

With the aim to investigate EPs in Mandarin Chinese, a major non-inflectional language outside the Indo-European family, this study will further elaborate on the abovementioned distinctions and inquire about the possible range of lexical-constructional associations that are semantically distinct and grammatically realized in the lexicon of emotion.

Specifically, this study attempts to probe into the semantic correlates of the possible grammatical variations to see if the contrasts manifested in English are universal and essential to EPs. It takes on three main questions: (1) How is emotion conceptualized and lexicalized in a non-European language such as Mandarin? (2) How do emotional predicates differ from each other? That is, what are the lexical-constructional variations displayed among EPs? (3) How can the study of EPs shed light on typological and theoretical issues in verbal semantics?

In its attempt to answer the above questions, the study will provide a cognitive semantic account of the range of lexicalization patterns attested in the Mandarin lexicon. The ultimate goal of the study is to identify reliable semantic-to-syntactic criteria for establishing the subclasses of the Mandarin EP inventory for further language-specific representation or cross-linguistic comparison.

1.3 Summary of findings

A closer examination of the major works on the lexical semantic distinctions of EPs reveals that besides the two commonly recognized participant roles, Experiencer and Stimulus, another semantically distinct and non-decomposable role, Affector, is also prominent in emotional predication, as it profiles a higher degree of volitional impact. Affector can be defined in relation to the notion of affectedness that is taken to be a scale of change the theme participant undergoes (Beavers 2011, 2013; Tenny 1987, 1992; Kenny 1963). Different from the non-sentient Stimulus, an Affector volitionally instigates an internal change on an Affectee in a more dynamic and eventive manner. With the postulation of Affector, a three-way distinction of lexicalization patterns is in place that is syntactically attested in Mandarin. Namely, EPs may lexicalize either an Experiencer, a Stimulus, or an Affector as the subject, with different implications of eventivity and degree of affectedness. The distinction of three types of subject roles correspond nicely to the three-way case distinction that surfaces in some Indo-European languages that have three different cases for EP subjects (see discussion in Section 2.2). It also helps to account for the stative vs. eventive distinction as mentioned above and illustrated in 5. The proposed three-role scheme thus provides a sound basis for lexical semantic categorization as well as cross-linguistic comparison. While verbs can be categorized into different subtypes based on subject role selection, languages may vary in terms of the predominant and preferred pattern of lexicalization as a particular role may be most frequently chosen in the emotion lexicon.

In view of the saliency of subject roles in determining the subtypes of EPs, the study further probes into the range of form-meaning mapping principles realized in polysemous relations as well as the grammatical means typically drawn upon to encode a subject role shift. It is found that the Chinese emotion lexicon is unique and differs from the known European languages in two respects. First, Chinese lacks readily lexicalized Stimulus-subject verbs, i.e., equivalents to English verbs such as interest, please, and frighten. Instead, a range of constructional templates are unutilized to derive Stimulus-subject EPs that are semi-lexicalized and morphologically-open. Secondly, Mandarin EPs display a unique spectrum of polysemous relations in that the same verb form may be associated with multiple subject roles and grammatical functions, demonstrating a heterogeneous range of form-meaning mismatches. It is interesting to note that the Chinese way of coining Stimulus-subject EPs via constructional modes and its lexical association with multiple usages both demonstrate that lexical and constructional entities are meaning-bearing units that constitute a continuum of form-meaning association along the same dimension, an important observation that is potentially in line with the theoretical premises of Construction Grammar (Goldberg 1995, 2005).

1.4 The proposal and organization

Based on the findings, the study eventually makes three main proposals: (1) There are three different subject roles (Experiencer, Stimulus, and Affector) that need to be distinguished for the classification of EPs in Mandarin; (2) Different from English, Mandarin tends to prefer lexicalizing Experiencer or Affector as subject as it lacks fully lexicalized Stimulus-subject verbsFootnote 3; (3) Given the three-way distinction, a language may be Experiencer-prominent, Stimulus-prominent, or Affector-prominent, depending on the relevant factors of constructional unmarkedness, lexical status, and distributional frequency. Languages can then be compared in terms of their predominant lexicalization patternsFootnote 4. By deciphering the collo-constructional variations across different lexical classes, the study ultimately shows that lexicalization works hand-in-hand with constructionalization in shaping the lexicon of emotion.

Following the Introduction, Section 2 reviews a series of studies on lexicalization patterns and semantic distinctions of EPs in English and other languages. Section 3 provides a preliminary account of Mandarin EPs and explores the lexical-constructional interactions characteristic of the Mandarin emotion lexicon. Section 4 discusses the form-meaning mismatches displayed in some particular classes of EPs. Section 5 outlines the preliminary typological distinction. Section 6 draws on theoretical implications and concludes the study. The analyses are mainly based on observations of corpus data from Sinica Balanced Corpus 5.0 of Modern Mandarin, supplemented with data from Chinese Gigaword CorpusFootnote 5. Whenever necessary, contrastive skeleton examples may be given for the sake of clarity.

2 Previous studies on lexicalization of emotion

In the following, major works on lexicalization patterns in English and other languages will be reviewed to lay a foundation for further comparison with Mandarin EPs. Factors involved in lexicalizing emotional predicates may include:

-

Selection of subject roles:

-

What gets to be lexicalized as the subject?

-

-

Case marking:

-

What kind of case distinction is found with EPs?

-

-

Argument expression:

-

What arguments are involved and how are they grammatically expressed?

-

-

Morphological variation:

-

What are the morphological variants pertaining to lexical classes?

-

-

Constructional derivation:

-

What kind of constructional association is found with what kind of EP?

-

-

Causal bases:

-

What are the causal bases (internal or external; inherent or directed) encoded in EPs?

-

2.1 Two-way distinction: subject selection

As already mentioned, the bipartite division between Experiencer-subject and Stimulus-subject EPs is most predominant in the literature. In his discussion of verbal valence, defined as the built-in constraints on a verb’s freedom to assign focus, or simply, the focusing properties of verbs, Talmy (2000: 98-99) categorizes the majority of English verbs of affect into two valence types as illustrated in 1 above. While verbs may lexically select either Experiencer or Stimulus as its default subject role, there are grammatical-derivational means for verbs of either type, to switch to the opposite type, as exemplified below (ibid.: 98)Footnote 6:

-

(6)

Switch of subject with grammatical-derivational means

Apparently, with a Stimulus-subject verb like frighten, English systematically utilizes grammatical derivations to allow an Experiencer to take the subject position. This pattern appears to be fairly productive, compared to the more limited pattern in deriving a Stimulus subject with a lexically Experiencer-subject verb like “fear”. This is why Talmy further argues (2000: 98) that “while possibly all languages have some verbs of each valence type, they differ as to which type predominates. In this respect, English seems to favor lexicalizing the Stimulus as subject.…The bulk of its vocabulary items for affect focus on the Stimulus.” In contrast to English, Atsugewi (a Native American language) was mentioned as having verb roots that exclusively take an Experiencer-subject. To express a Stimulus-subject in this language, a suffix –ahẃ has to be added to the verb root.

Talmy’s dichotomy of emotional valence in terms of subject selection serves as a preliminary and convenient scheme to categorize the emotional lexicon. However, as Talmy (2000: 99) cautions, the boundaries of the “affect” category may be too “encompassive or misdrawn” and there may be “smaller categories following more natural divisions that reveal more about semantic organization.” And indeed, EPs are semantically heterogeneous and more complex distinctions are proposed in other works as summarized below.

2.2 Three-way distinction: case marking

Filip (1996) reported a three-way case marking distinction found in Czech and other related Indo-European languages. The Experiencer participant may take three morphological cases: nominative, accusative or dative, giving rise to three different subclasses of EPs (ibid.: 136-137):

-

(7)

Three different case markings on Experiencer in Czech:

-

a.

Nominative-Exp

Václav__miluje__Marii.

Václav-NOM__love__Mary-ACC

[Václav] NOM loves Mary.

-

b.

Accusative-Exp

Václav__baví__Marii.

Václav-NOM__amuse__Mary-ACC

Václav amuses [Mary] ACC .

-

c.

Dative-Exp

Václav__schází__ Marii.

Václav-NOM__lack__Mary-DAT

[Mary] DAT misses Václav. (lit.: Václav lacks [to Mary]).

-

a.

As Filip further mentioned, a similar tripartite division in case marking can be found in other Indo-European languages, including French (Legendre 1989), Italian (Perlmutter 1984; Belletti and Rizzi 1988), Dutch (Zaenen 1988), Russian (Holloway-King 1993), Bulgarian (Slabakova 1994), and in South Asian languages (cf. Verma and Mohanan 1990). The three lexical classes are further accounted as displaying different clusters of semantic features along the Proto-Agent vs. Proto-Patient paradigm (Dowty 1991). Two of the salient Proto-Agent properties, “sentience” and “volition,” are taken to be the crucial motivation for the nominative case marking, while the accusative and dative case markings imply a lack of control or a low degree of control on the part of the Experiencer, displaying more Proto-Patient characters as being affected under the direct or indirect force of an external Stimulus.

A finer distinction, as Filip pointed out, is that only the sentence with an accusative-Experiencer is taken to be eventive, distinct from the stative use of a nominative or dative Experiencer. To obtain an eventive reading with a nominative subject, 7a has to be modified into a reflexive with an accusative form as followsFootnote 7:

-

(7a’)

Eventive reading with accusative reflexive

Václav__se__za-mil-oval__do__Marie.

Václav-NOM__REFL.ACC__ PFV-love-3p.sg.masc.PST__in__Mary-GEN

[Václav] fell in love with Mary. (lit., Václav loved himself into Mary.)

The stative verb in 7a’ with the perfective prefix renders an inchoative reading. It is apparent that an eventive reading in Czech is aligned with the accusative marking of the Experiencer, which is comparable to the eventive use of Stimulus-subject verbs in English, as illustrated in 5b above. The accusative case in Czech can be viewed as a morphological correlate to eventive predication that Dowty (1991:580), following Croft (1986), interpreted as “inchoative” in the sense that it implies a change of state on the Experiencer as it comes to experience a new mental state. She further argued that the inchoative or eventive interpretation entails a Proto-Patient property in relation to a volitional, affective agent. The affective agent plays an active role in instigating the change of state that can be viewed as realized or “measured” by the eventive assertion (Tenny 1987, 1992). It thus correlates to a higher degree of affectedness, as defined in Beavers (2011, 2013). The realized change or affectedness suggests that there is a more dynamic and impacting subject involved than the static notion of Stimulus. Taking the subject roles into consideration, the Czech examples suggest a potential three-way distinction in relation to eventivity and affectedness:

-

(8)

A three-way distinction in lexicalizing emotion:

-

a.

Stative with Experiencer as subject: Experiencer in nominative case (Czech and English), Stimulus as direct object

-

b.

Stative with Stimulus as subject: Experiencer as indirect object in dative case (Czech) or as direct object in stative predication (English)

-

c.

Eventive with more Proto-Agent subject and Proto-Patient object: Experiencer as direct object in accusative case (Czech) and in more eventive predication (English)

-

a.

The three-way distinction proposed indicates the presence of a separate thematic role from the traditional notion of Stimulus. A more dynamic and agentive role is apparently involved in the inchoative or eventive version. To highlight its affective role, this type of subject can be called Affector, which instigates a change on the object, the Affectee, which undergoes the change, as marked with accusative case in Czech. The Affector plays a similar role as what is termed “Effector” in Van Valin (2005), a more fundamental notion than Agent that underpins the basic properties of a volitional and acting instigator. More detailed discussion will be given in Section 3.

2.3 Four-way distinction: argument expression

Levin (1993: 188-193) acknowledged the fact that EPs (or psych-verbs in her terms) typically take two arguments with their semantic roles frequently characterized as Experiencer and Stimulus. But in terms of argument expressions, it is possible to distinguish four subclasses: (1) amuse verbs: transitive verbs describing the bringing about of a mental change, with the cause of the change as the subject and the Experiencer as the object, e.g., The crown amused the children; (2) admire verbs: transitive verbs with an Experiencer subject, e.g., The tourists admire the paintings; (3) marvel verbs: intransitive verbs with an Experiencer subject and a Stimulus in a prepositional phrase, e.g. She marveled at the beauty of the Grand Canyon.; and (4) appeal verbs: intransitive verbs taking the Stimulus as subject and expressing the Experiencer in a prepositional, e.g. This painting appealed to her. The last class, according to Levin, is the smallest and resembles a prevalent pattern in other languages like Czech, with a nominative Stimulus and a dative Experiencer. The four contrastive classes are differentiated on two variables: selection of subject role (Stimulus or Cause vs. Experiencer) and argument structure (transitive vs. intransitive), as summarized below:

-

(9)

Four-way distinction on English psych-verbs:

-

a.

amuse verbs: transitive, Cause as subject, Experiencer as object

-

b.

admire verbs: transitive, Experiencer as subject, Stimulus as object

-

c.

marvel verbs: intransitive, Experiencer as subject

-

d.

appeal verbs: intransitive, Stimulus as subject

-

a.

It is noted that Levin chose the term “cause,” instead of stimulus, in describing the subject of the amuse group of verbs by saying “they are transitive verbs … whose subject is the cause of the change in psychological state” (1993: 191). She then indicated, following Grimshaw (1990), that some of these verbs, such as amuse, allow the subject argument to receive an agentive interpretation, while others, such as concern, do not. This distinction, as further suggested by Levin, could be the basis for further subdivision of this group of verbs. And indeed, as we already seen in the Czech examples, the agentive interpretation of the subject suggests a semantically distinct “causer” role that is termed Affector in this paper.

2.4 Five-way distinction: morphological variants

To include adjectival EPs, Jackendoff (2007:220-221) made finer morphological and semantic distinctions for what he called “psychological predicates” in English. Under the assumption that verbal and adjectival EPs share the same predicational function, he arrayed five distinct types of morphological variants, from highly foregrounding the Experiencer to highly foregrounding the StimulusFootnote 8:

-

(10)

Morphological variants of English psychological verbs and adjectives:

-

a.

Exp-Adj I’m bored.

-

b.

Exp-Adj-Stim I’m bored with this.

-

c.

Exp-Verb-Stim I detest this.

-

d.

Stim-Verb-Exp This bores me.

-

e.

Stim-Adj-(Exp) This is boring (to me).

-

a.

Under the assumption that “morphologically related items often share a semantic core” (Jackendoff 2007: 224), the various frames are related with a conceptual basis as sharing the semantic function of X BE [Property Y]. Four specific points were made that are most relevant to the present study. First, the distinction between Experiencer-subject adjectives in 10a and 10b lies in the distinction between inherent meaning (I’m just plain bored) and directed meaning (*I’m just plain interested). Citing Ekman and Davidson (1994), Jackendoff asserts that certain emotional experiences are “pure feelings,” independent of surroundings, such as happy, sad, calm, nervous, scared, and upset; but most others are directed emotions such as being attracted, disgusted, interested, and humiliated. The contrast is illustrated below (ibid.: 224):

-

(11)

Inherent vs. directed feelings:

-

a.

Inherent: I’m not bored with anything in particular, I’m just (plain) bored.

-

b.

Directed: *I’m not interested in anything in particular, I’m just (plain) interested.

-

a.

This meaning distinction interacts with grammatical forms and underlines the argument structure of Experiencer-subject adjectives, since inherent feelings will not require the presence of a Stimulus as shown in 10a, but Stimulus is required and cannot be left out in 10bFootnote 9. As will be clear in the next section, this lexical semantic distinction also bears grammatical consequences in Mandarin and it is significant in fine-tuning Mandarin near-synonyms.

Secondly, the Exp-V-Stim frame in 10c is considered to be conforming to the same predication template with the adjectival use as it “incorporates” the predication function BE. In other words, the English verbal use is semantically similar to the adjectival use. This analysis is of particular interest to the Mandarin lexicon, since Mandarin does not draw a clear line, morphologically, syntactically, and semantically, between stative verbs and adjectives. In view of Jackendoff’s analysis, stative verbs and adjectives share the same semantic function BE and thus help to justify the null distinction between verbal vs. adjectival predicates in Mandarin.

Thirdly, the adjectival frames, Exp-Adj-Stim in 10b and Stim-Adj-(Exp) in 10e, are taken as describing the same situation, since the adjective with a Stimulus subject (e.g., Golf is interesting to Bob) is derived as a paraphrase of the Experiencer-subject adjective (Bob is interested in Golf), with the so-called lambda-abstraction: Golf is such that Bob is interested in it. The paraphrase is formally achieved with the effect of marking the Stimulus as prominent (see Jackendoff 2007: 228 for details). Interestingly, the suggested semantic connection between Experiencer-subject and Stimulus-subject frames is also realized in Mandarin. The same verb can be used for both purposes with a constructional shift.

Finally, the transitive Stim-Verb-Exp frame (This bores me.) in 10d is treated as conceptually synonymous with the adjectival frame (This is boring (to me).) in 10e, as they are both causative in nature (cause X to BE). Their conceptual similarity in causality is grammatically realized in Mandarin as the causative pattern is commonly used to predicate a Stimulus-subject in either transitive or intransitive use, as will be detailed in Section 3.1.

With reference to Pesetsky (1995), Jackendoff (ibid.: 234) suggested that the causal relation with a Stimulus-subject can be fine-tuned with four types of lexical variants:

-

(12)

Lexical variants with the frame ‘Stimulus-Verb-Experiencer’:

-

a.

Noncausative with Stimulus subjects (appeal to, matters to, please, interest):

The news appeals to Sam.

-

b.

Causative with agent subjects and Stimulus as extra argument:

The news pissed Sam off at the government.

-

c.

Causative with agent subjects, necessarily identical with Stimulus (attract, repel):

The news attracts Sam.

-

d.

Causative with agent subjects, defeasibly identical with Stimulus (frighten, depress, excite):

The news frightens Sam.

-

a.

In distinguishing the four variants, Jackendoff takes “causative” as having an agent subject, which may or may not be identical with a Stimulus. The agent subject serves as an affecting causer that impacts the Experiencer and makes it more like a patient. This is in line with the role hierarchy proposed in Pesetsky (1995): Causer > Experiencer > Target (or subject matter). Pesetsky’s notion of Causer can be either an agentive or presumably non-agentive Stimulus subject. The more agentivity is perceived on the Causer, the more affectedness is rendered on the Experiencer, who resembles an undergoer of impact without much controlFootnote 10. Judged by the varied degrees of impact on the Experiencer, it is clear that the agentive subject can be distinguished and separately considered from the non-sentient Stimulus. This supports the postulation of an agentive subject role (the Affector), accompanied with a patient-like object role (the Affectee). Again, the functional correlation observed in English is grammatically confirmed in Mandarin.

What is striking here is that most of the semantic implications postulated in Jackendoff (2007) may find grammatical evidence in Mandarin. It will be shown in subsequent discussions that the distinction between Experiencer-subject EPs (inherent vs. directed feelings as in 11) can be further elaborated with studies on Mandarin near-synonym sets of Experiencer-subject EPs since they are abundant and semantically fine-grained in Mandarin. And, it will be clear that Stimulus-subject predication in Mandarin essentially involves finer distinctions of causal relation, since it is overtly expressed with a marked causative construction (Stimulus as causer).

2.5 Distinction of near-synonyms: causal and constructional variation

A number of pioneering works on Mandarin emotion lexicon looked specifically into the syntax-semantics interface manifested in Experiencer-subject EPs, with a focus on commonly recognized near-synonym sets (1999; Chang et al. 2000; Liu 2002). These works aim to discover the fine-grained semantic distinctions from a corpus-based approach. Among them, Tsai et al. 蔡美智等 (1999) examined the frequently used pair of verbs, 高興 gaoxing “be glad, pleased” and 快樂 kuaile “be happy, content”. It is found that 高興 gaoxing displays a higher frequency in predicative use (vs. nominal use), eventive adverbials, and causal complements. Based on distributional differences in nominalization, adjectival/adverbial modification, and sentential complement, the study proposed that the two verbs differ with a semantic distinction in inchoative vs. homogeneous state (ibid.: 449-453). The distinction is further decomposed into two semantic features: change of state and control. The verb 高興 gaoxing represents an inchoative state with higher degree of experiencer control and is thus lexically specified with the features <+change of state, +control>, while 快樂 kuaile, represents a homogeneous state with less volitional control and is thus characterized as <−change of state, −control>.

Following up on the above study, Chang et al. (2000) looked at more sets of Experiencer-subject EPs and proposed a morphological account for the systematic variation between inchoative vs. homogeneous state verbs. Seven semantic fields of emotional sentience are distinguished, including happiness, worry, fear, anger, regret, sadness, and depression. For each field, two representative lemmas are examined as a contrastive pair. Based on distributional criteria, verbs in each field are divided into two semantic types: (1) type A (inchoative state): 高興 gaoxing “become glad/pleased,” 難過 nanguo “become sorrowful,” 後悔 houhui “regret,” 傷心 shangxin “get heart-broken,” 生氣 shengqi “get angry,” 害怕 haipa “get scared,” 擔心 danxin “get worried”; (2) type B (homogeneous state): 快樂 kuaile “be happy,” 痛苦 tongku, “be painful,” 遺憾 yihan “be sorry,” 悲傷 beishang “be sad,” 憤怒 fennu “be full of anger,” 恐懼 kongju kong “fear,” 煩惱 fannao “be perplexed”.

The semantic types with their paradigmatic differences in grammatical distribution are further attributed to morphological differences: type A verbs are mostly non-VV compounds (e.g., Manner-V for 高興 gao-xing “high-excite” and 難過 nan-guo “difficult-pass”) and type B verbs are VV compounds (e.g., 快樂 kuai-le “cheer-merry,” 痛苦 tong-ku “ache-suffer”). The VV compounds combine two synonyms (or antonyms) to represent a functionally uniform kind of emotion, which is semantically more homogeneous and time-stable. On the other hand, non-VV compounds may involve a skewed combination of functionally distinct elements (Manner + Verb or Verb + Goal) and are prone to predicate a change of state or inchoative event.

However, there are still near-synonyms that belong to the same morphological type; for example, the Mandarin equivalents of envy and be jealous of are both VV compounds. Liu (2002) explored this transitive set of near-synonyms, 羨慕 xianmu “envy/be envious of” vs. 忌妒 jidu “be jealous of,” and proposed an account for their semantic as well as pragmatic distinction. It is found that besides the typical unmarked transitive pattern, the verbs can both occur in a causative pattern overly marked by one of the causative markers (讓 rang, 令 ling, 使 shi, or 叫 jiao)Footnote 11:

-

(13)

The Transitive-Causative alternation:

-

a.

Transitive pattern: Experiencer as Actor

我羨慕/忌妒他

wo__xianmu/ jidu __ta

1p.sg__envy/jealous__3p.sg

I envy him.

-

b.

Causative pattern: Stimulus as Causer

他讓我羨慕/忌妒

ta__rang__wo__xianmu/jidu

3p.sg__cause__1p.sg__envy/jealous

He made me envious.

-

a.

The Stimulus-as-Cause construction highlights an external cause that is important in distinguishing the meanings of the two verbs. Liu (ibid.) further distinguishes two types of caused events, adopting the analysis of verbs of sound in Atkins et al. (1996). Similar to sound emissions, emotional experiences can be externally or internally caused, which also bears pragmatic implications. The socially more acceptable verb 羨慕 xianmu “envy” is taken to be externally caused as it has a higher percentage of verbal use and tends to collocate with an externally describable cause, which may serve as a social justification of the emotion. In contrast, the less acceptable counterpart 忌妒 jidu “be jealous of” is internally-caused, as it is has a higher percentage of nominal, non-causal use and if a cause is ever present, it is typically an inner, non-describable cause, such as 心 xin in 心生忌妒 xin-sheng-jidu “jealousy from within”. The absent or incommunicable cause makes it hard to be socially justifiable.

Liu (2002)’s proposal of internally vs. externally caused emotions may provide a principled account to integrate the distinction between inchoative vs. homogeneous state in Tsai et al. 蔡美智等 (1999) and the division of type A vs. type B verbs in Chang et al. (2000). Inchoative states or type A verbs are externally caused, as they involve a higher degree of volitional control with verbal use and more overt mention of an externally present cause. On the other hand, homogeneous states or type B verbs are internally caused, involving a higher percentage of nominal use with less volitional control and less mention of a describable cause.

The proposed analysis also goes nicely with the distinction of inherent vs. directed feelings (bored vs. interested), proposed in Jackendoff (2007) and illustrated in 11 above. As Jackendoff asserts, inherent feelings are “pure emotions” that are independent of the external surroundings and thus may not require an external cause (i.e., internally caused in Liu (2002)’s terms), while directed feelings require the mention of an external stimulus (i.e., externally caused). This fine-grained distinction is applicable to most Experiencer-subject predicates, transitive or intransitive.

Based on findings on cultural universals (Ekman and Davidson 1994), Jackendoff further states that the difference between inherent vs. directed feelings is psychologically founded and “does not appear to have anything to do with language” (Jackendoff 2007:225). It is clear that this semantic distinction may be universal and cross-linguistically applicable, as also evidenced in Mandarin.

In sum, the works reviewed in Section 2 indicate important findings regarding the six crucial factors that are involved in the lexicalization of emotional events, as summarized below:

-

(14)

Factors involved in lexicalizing emotional predicates:

-

a.

Selection of subject roles: What gets to be lexicalized as the subject?

-

Traditionally, only Experiencer and Stimulus are distinguished in Talmy (2000), but to capture finer semantic distinctions, the role of Affector may be needed.

-

-

b.

Case marking: What kind of case distinction is found with EPs?

-

Three cases (nominative, accusative, dative) can be distinguished for the human Experiencer in Czech (Filip 1996), indicating a three-way role distinction.

-

-

c.

Argument expression: What arguments are involved and grammatically expressed?

-

On the surface, a four-way distinction is observed for subject role (Experiencer vs. Stimulus) and argument realization (transitive vs. intransitive) in Levin (1993). But some transitive-Stimulus EPs allow an agentive reading of the subject, indicating a different role on the causal subject, which is also related to the stative vs. eventive distinction.

-

-

d.

Morphological variation: What are the morphological variants pertaining to lexical classes?

-

Five morphological variants are distinguished for English in Jackendoff (2007), taking into consideration of both verbs and adjectives but disregarding the transitive vs. intransitive argument distinction. However, the verbal vs. adjectival morphological distinction may be blurred in a non-inflectional language such as Mandarin (see Section 3.1).

-

-

e.

Causal bases: What are the causal bases (internal or external; inherent or directed) for EPs?

-

f.

Constructional derivation: What kind of construction is associated with what kind of EPs?

-

Subject role shift is accompanied with constructional shift. While morphological derivation clearly indicates such a shift in English, Mandarin uses the overt causative pattern for expressing a Stimulus-Cause, as seen in 13b. It will be clear in the next section that Mandarin lacks Stimulus-subject EPs and constantly resorts to a causative construction when the subject switches to a Stimulus.

-

-

a.

What follows is a close examination of the factors in relation to the Mandarin emotion lexicon, which will provide a more complete picture to address the original concern: what is unique in the lexicalization of Mandarin EPs? To what extent and in what way can the observed lexicalization patterns be considered cross-linguistically relevant?

3 Emotional predication in Mandarin: lexical-constructional interactions

3.1 Preliminaries

As an initial introduction of the emotion lexicon in Mandarin, some preliminary accounts are given here with reference to the formal contrasts in English mentioned in Section 1. The most noticeable difference is that there is no morphological distinction between verbal vs. adjectival EPs in Mandarin, since stative verbs and adjectives are formally identical. There is, nevertheless, an important and consistent grammatical distinction between stative vs. eventive predication (cf. Chao 1968; Li and Thompson 1981). Stative predicates are compatible with degree modification, typically taking the default degree modifier 很 hen “very, fairly,” as a crucial indicator of scalar evaluation (Liu and Chang 2012)Footnote 12. As exemplified below, most EPs (such as 羨慕 xianmu “envy”) tend to occur with the evaluative marker 很 hen, which is an indicator of stativity and less compatible with a telic physical action verb (such as 打 da “hit”)Footnote 13. On the other hand, a stative EP is less compatible with the eventive, verb-final perfective marker 了 le, which marks the actualization of a temporally bounded event (Liu 2015):

-

(15)

Stative predicates with degree marker 很 hen

我很羨慕/*打他

wo__hen__xianmu/*da __ta.

1p.sg__DEG__envy/hit__3p.sg

I quite envy/*hit him.

-

(16)

Eventive predicates with perfective marker 了 le

我打/*羨慕了他

wo__da/* xianmu__le__ta.

1p.sg__hit/*envy__LE__3p.sg

I hit him/*(done) envied him.

The majority of Mandarin EPs are stative in nature as they are compatible with degree evaluation. But a degree marker is not obligatory with stative EPs, if the verbal use is to be stressedFootnote 14. Given that there appears to be a functional division between 很hen “quite, fairly,” marking evaluative predication, and the perfective/inchoative marker 了 le, marking eventive predication, EPs can be divided as to their co-occurrence preference with the two markers. Lexical variations can be found with a group of Stimulus-subject verbs that tend to align more with eventive predication, indicating a semantic departure from stativity, which will be further discussed in the next section.

Given that there is no morphological difference between stative verbs and adjectives in Mandarin, the verbal vs. adjectival contrast lexically coded in English (envy vs. be envious of, as illustrated in 2 above) is formally neutralized and indistinguishable in Mandarin. For example, the abovementioned EP 羨慕 xianmu can be taken as either “envy” or “be envious of,” especially with the presence of a degree marker.

Along with the neutralization of verbal vs. adjectival distinction, the transitive vs. intransitive contrast that is strictly lexicalized in English is also relaxed in Mandarin. The different behaviors of Mandarin EPs can be discussed in relation to subject-role selection. First, Experiencer-subject EPs are more prominent and abundant in Mandarin. They correspond nicely to the English Experiencer-subject verbs. Although the majority of them are lexically specified to be either transitive or intransitive, some of them can be used in both ways (with or without a direct object) and allow flexible argument expression. First presented below are some examples of clearly transitive or intransitive EPs:

-

(17)

Experiencer-subject EPs:

-

a.

Intransitive:

-

我很生氣/緊張/沮喪

-

wo__hen__shengqi/jingzhang/jusang.

-

1.sg__DEG__pleased/nervous/depressed.

-

I am angry/nervous/depressed.

-

-

b.

Transitive

-

我很喜歡/欣賞/討厭他

-

wo__hen__xihuan/xingshang/taoyan__ta

-

1.sg__DEG__admire/like/dislike__3p.sg

-

I like/admire/dislike him.

-

-

a.

The transitive EPs, such as 欣賞 xingshang “admire,” normally denote a directed feeling that require the presence of a direct object, typically taking up the postverbal position. But the object may occasionally be expressed preverbally as an indirect Goal argument, marked by the goal marker 對 dui “to”. When this happens, the transitive vs. intransitive distinction may be blurred, since intransitive EPs denoting a directed feeling (such as 生氣 shengqi “angry”) may also take an indirect goal:

-

(18)

Indirect goal with transitive and intransitive EPs

-

我對他很生氣intr/欣賞tr

-

wo__dui__ ta__hen__shengqi/xingshang

-

1p.sg__to__3p.sg__DEG__angry/admire

-

I am angry at/admire him.

-

More importantly, the transitive vs. intransitive contrast can also be blurred with a small group of Experiencer-subject EPs that may denote inherent or directed feelings. These EPs may be used transitively or intransitively, without any change on lexical forms:

-

(19)

The same Exp-subject verb for intransitive and transitive uses:

-

a.

Intransitive:

我很害怕/擔心

wo__hen__haipa/danxin.

1p.sg__DEG__scared/worried

I am scared/worried.

-

b.

Transitive:

我很害怕/擔心他

wo__hen__haipa/danxin__ta

1p.sg__DEG__fear/worry__3p.sg

I fear/worry (about) him.

-

a.

While Experiencer-subject verbs are abundant and diverse in Mandarin, the picture of Stimulus-subject verbs is totally different. It is difficult and problematic to find lexical equivalents of the majority of English Stimulus-subject verbs, such as please, excite, frustrate, in the Mandarin lexicon. Although a few Stimulus-subject verbs can be found as exemplified below, the Mandarin lexicon in general dis-prefers to lexicalize a Stimulus as subject.

-

(20)

Stimulus-subject EPs:

-

a.

Intransitive

-

這本書很枯燥/有趣/恐怖

-

zhe-ben__shu__hen__kuzao/youqu/kongbu

-

this-CL__book__DEG__dull/fun/horrible

-

The book is dull/interesting/dispiriting.

-

-

b.

Transitive

-

這本書很吸引/感動/激勵我

-

zhe-ben__shu__hen__xiyin/gandong/jili__wo.

-

this-CL__book__DEG__attract/touch/encourage__me

-

The book attracts/touches/encourages me.

-

-

a.

The EPs listed here are among the few Stimulus-subject verbs that are fully lexicalized and ready to predicate a Stimulus. However, to express “He pleases me” in Mandarin, no lexicalized verb can be readily used to render an equivalent transitive sentence. Mandarin has to resort to a causative pattern that converts an Experiencer-subject verb into the Stimulus-predicating construction, as shown below:

-

(21)

他讓我很高興/興奮/挫折

ta__rang__wo__hen__gaoxing/xingfen/cuozhe.

3p.sg__CAU__1p.sg__DEG__pleased/excited/frustrated

He made me pleased/excited/frustrated.

The causative construction is overtly marked with a causative morpheme, 讓 rang, 令 ling, 使 shi, or 叫 jiao Footnote 15, which serves to signal the causal relation whereby a Stimulus-causer “causes” an Experiencer-causee to be in an emotional state, expressed by an Experiencer-subject EP. This causative pattern is highly productive in Mandarin and semantically requires a Stimulus as the subject-causerFootnote 16 and an Experiencer as the object-causee. As also seen in 13 above, Experiencer-subject EPs can all enter the construction when a Stimulus takes on the subject-causer position. What is more revealing is that in order to coin the adjectival counterparts of the missing verbs, such as pleasing, exciting, and disappointing, the causative template can be “simplified” with a morphologically preserved generic human noun 人 ren “person,” in the form of [CAU-person-VExp-subj]:

-

(22)

這個消息令人高興/令人興奮/令人失望

zhe-ge__xiaoxi__ling-ren-gaoxing/ling-ren-xingfen/ling-ren-shiwang

this-CL__news__CAU-person-pleased/CAU-person-excited/CAU-person-disappointed

The news is pleasing/exciting/disappointing.

Due to the lack of Stimulus-subject verbs in Mandarin, the causative pattern is utilized as a grammatical strategy to allow the shift of subject roles. What we see here is that while Stimulus-subject predication is lexically encoded in English, it is mostly done at the constructional level in Chinese. This points to an interesting and significant departure in lexicalization patterns, as will be further discussed in the section on subject role shift.

The preliminary introduction shows some unique features of Mandarin EPs. First, degree modification is compatible with Mandarin emotion predication, neutralizing the difference between stative verbs and adjectives. This prepares further discussion of the stative-eventive distinction that may be lexically distinguished in Mandarin. Secondly, Mandarin seems to allow more flexibility in argument expression and one lexical form may be mapped to more than one grammatical function, which leads to a further discussion of the range of form-meaning mapping relations manifested in polysemous EPs. Thirdly, Chinese is apparently more limited in lexicalizing Stimulus-subject verbs and it utilizes constructional means to remedy the missing link, which leads to a further discussion of the lexical-constructional variations characteristic of the Mandarin emotion lexicon.

3.2 Formal marking of the stative vs. eventive distinction

Relevant to the formal marking of semantic distinctions captured in 14 above, Mandarin has a more obvious way to mark the stative vs. eventive distinction. Given that stative EPs are evaluative in nature and there is no morphological distinction between verbal and adjectival uses, the presence or absence of a degree marker, given its scalar nature as discussed in Kennedy and McNally (2005), seems to be the key indicator for a more gradable adjectival use or a more eventive verbal useFootnote 17. In the corpus, the majority of EPs take some kind of degree adjunct, either preverbally or postverbally. Below are two more examples of degree marking:

-

(23)

Degree modification with intransitive EPs:

-

a.

Preverbal:

-

那位阿婆非常生氣

-

na-wei__apo__feichang__shengqi.

-

that-CL__old__woman__extraordinarily__angry.

-

That old woman was extraordinarily angry.

-

-

b.

Postverbal:

-

阿滿心中委屈萬分

-

aman__xin-zhong__weiqu__wanfen

-

NAME__heart-in__wronged__deeply

-

Aman was deeply aggrieved in his heart.

-

-

a.

Intransitive EPs are used predominantly with a degree marker or a resultative extent. Over the 617 predicate uses of 高興 gaoxing “be glad, pleased” in Sinica Corpus, less than 6 % (35 out of 617) of the cases do not have a degree marker or a resultative complementFootnote 18. Transitive EPs tend to be more equally distributed with or without degree modification. Among the 114 tokens of 羨慕 xianmu “envy” in Sinica Corpus 3.0, about 40 % of them (47 out of 114) take some sort of a degree marker. When the degree marker is absent, the predication is taken to be more eventive and change-related:

-

(24)

Cases without 很 hen “very, fairly”:

-

a.

Inchoative change

客人高興了,會賞你錢

keren__gaoxing__le, hui__shang__ni__qian.

customer__glad__LE, will__offer__you__money

If the customer is pleased, (he) will offer you a big tip.

-

b.

Transitive relation

他羨慕院子裡的大公雞

ta__xianmu__yuanzi__li__de__da-gongji

3p.sg__envy__yard__in__DE__big-rooster

He envied the rooster in the yard.

-

a.

The presence of the degree modifier is a clear indicator of stativity, which is in line with Jackendoff’s observation that emotional predicates share the semantic core [BE X]. While the majority of Mandarin EPs are stative and compatible with the degree-evaluative 很 hen, there is, however, a special group of EPs that may be lexically eventive. These verbs are morphologically verb-resultative (V-R) compounds, such as 激怒 jinu “irritate,” 惹火 rehuo “infuriate,” 惹惱 renao “provoke,” which may not occur so readily with a degree marker, but often collocate with the perfective or inchoative aspect marker le:

-

(25)

Eventive verbs with agentive subject:

-

a.

??這個消息很激怒/惹火/惹惱他

??zhe-ge__xiaoxi__hen__jinu/rehuo/renao__ ta.

this-CL__news__DEG__irritate/infuriate/provoke__3p.sg.

#This news highly irritated/infuriated/provoked him.

-

b.

這個消息激怒/惹火/惹惱了他

zhe-ge__ xiaoxi__jinu/rehuo/renao__le__ta.

this-CL__news__irritate/infuriate/provoke__LE__3p.sg.

This news irritated/infuriated/provoked him.

-

a.

These verbs exemplify the lexicalized predicates that morphologically encode a salient impact or change of state in the form of V-RFootnote 19, which is semantically less compatible with the indicator of stativity (很 hen), but prefers the inchoative/perfective aspectual marker 了 le. The V-R compounds stand out as a distinct set of EPs that are semantically eventive with a lexically assured change of state, normally indicating a higher degree of agentivity and affectedness. Although the subject may not always be human and volitional, the transitive event constantly collocates with the aspectual marker 了 le, which is associated with eventive predication and profiles a temporal boundedness. This group of EPs shows that the Mandarin emotion lexicon is sensitive to the stative-eventive distinction as already mentioned and illustrated in 5 above.

Moreover, the semantic distinction can be best illustrated with another group of Stimulus-subject EPs which are morphologically V-V compounds, such as 吸引 xiyin “attract,” 刺激 ciji “stimulate,” and 打擾 darao “bother.” These verbs may be stative or eventive, depending on the actual use:

-

(26)

Stimulus-subject transitive verbs:

-

a.

Stative with degree marker 很 hen

這件事很吸引/刺激/打擾他

zhe-jian__shi__hen__xiyin/ciji/darao__ta.

this-CL__matter__DEG__attract/stimulate/bother__3p.sg

This matter quite attracts/stimulates/bothers him.

-

b.

Eventive/inchoative with perfective marker 了 le

這件事吸引/刺激/打擾了他

zhe-jian__shi__xiyin/ciji/darao__ le__ ta.

this-CL__matter__attract/stimulate/bother__LE__3p.sg

This matter attracted/stimulated/bothered him.

-

a.

This stative vs. eventive semantic distinction may be lexically implicit in English, but it is more explicitly encoded in Mandarin, corresponding to morphological and constructional differentiations. What needs to be noted here is that the lexicalized eventive verbs in the form of V-R must denote a different semantic relation from the traditional Stimulus-to-Experiencer relation.

As shown in the following example, there seems to be a gradation from highly stative to highly eventive predications that can be formally distinguished with lexical-constructional variations in Mandarin. In the following examples, the converted causative use of a stative Experiencer-subject verb 害怕 haipa “fear” is put in contrast to the three different uses of an inherently eventive verb 嚇 xia “scare, frighten, startle,” ranging from indirect causation, to direct transitivity, and to volitional deliberation. The verb 嚇 xia collocates constantly with an event instantiation phase marker —跳 yi-tiao “one-jump” to predicate an individuated event that can be expressed in a stative, causative pattern with a Stimulus-causer and Experiencer-causee 27b, in a eventive, transitive pattern with a directly affected object 27c:

-

(27) a.

打雷讓老王害怕

dalei__rang__lao-wang__haipa

thunder__CAUSE__Old-Wang__frightened

Thunder causes Old-Wang to have fear.

-

b.

打雷讓老王嚇了一跳

dalei__rang__lao-wang__xia__le__yi-tiao

thunder__CAUSE__Old-Wang__scare__LE__one-jump

Thunder made Old-Wang scared with a jump.

-

c.

打雷嚇了老王一跳

dalei__xia__le__lao-wang__yi-tiao

thunder__scare__LE__Old-Wang__one-jump

Thunder startled Old-Wang with a jump.

The direct impact encoded in the verb can be seen more clearly from the volitional use with a deliberating human agentFootnote 20:

-

(28)

Volitional uses of 嚇xia with human subjects:

-

a.

他故意嚇老王, 但是沒嚇到

ta__guyi__xia__lao-wang, danshi__mei__xia-dao.

3p.sg__deliberately__scare__Old-Wang, but__NEG__scare-arrive

He deliberately tried to scare Old Wang, but did not succeed.’

-

b.

不要嚇我!

buyao__xia__wo

don’t__scare__1p.sg

Don’t scare me!

-

a.

Relevant to the questions raised in 14, the range of semantic variations illustrated above is manifested with a range of lexical-constructional variations. Such variations are motivated by a gradation from highly stative to highly eventive distinctions in the uses of Mandarin EPs. In the last example with a human subject, it is quite clear that the subject plays a more volitional and instigating role, different from the non-active, non-sentient role of a Stimulus. This role distinction is relative to the extent of affectedness instilled on the theme participant and should be recognized as a lexical semantic distinction. As will be clear in the discussion of the thematic relation involved, the volitional subject may be more appropriately viewed as an Affector, if not a prototypical agent.

3.3 Constructional variation with subject role shift

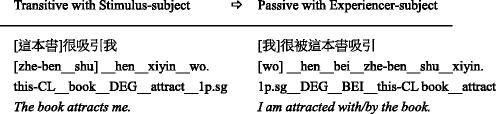

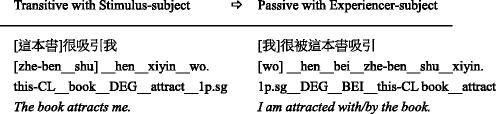

As already seen clearly, the selected role of the subject is a crucial factor in the classification of emotional predicates. Different subject roles will trigger different lexical and constructional patterns. When the subject role is shifted, languages may resort to various grammatical means to signal the accompanied semantic shift. English, as an inflectional language, makes heavy use of derivational morphology to signal semantic correlations (e.g. interesting vs. interested). In an analytic language like Mandarin, it is constructional variation that is heavily used to signal the change. Thus, subject role shift is directly accompanied with constructional alternation. As already mentioned above, an Experiencer-subject predicate normally occurs in the stative-evaluative construction, typically marked by a degree marker in the form [Exp-DEG-Verb]. And when the subject shifts to a Stimulus, an overt causative construction is used, with a causative marker 讓 rang, 令 ling, 使 shi, or 叫 jiao, in the pattern [Stim-CAU-Exp-DEG-V]. For stative predication, the subject role shift is accompanied with a constructional alternation from stative to causative constructions:

-

(29)

Stative-Causative alternation

As noted earlier, the causative construction is productive and constantly drawn upon to coin the missing Stimulus-subject EPs, due to the lack of lexical Stimulus-subject verbs such as please, excite, and interest. The closest equivalents of pleasing, exciting and interesting are semi-lexicalized causatives, derived from the causative template with a generic causee in the form [CAU-person-V], such as 令人高興 ling-ren-gaoxing [CAU-person-happy], for “pleasing”. This impersonal causative pattern behaves like other stative predicates since it can also take a preceding degree marker such as 很 hen Footnote 21, but it is not yet fully lexicalized (see discussion in Section 3.5). It provides a grammatical means for shifting the subject role from Experiencer to Stimulus while maintaining a semantic link using the same verb.

What is more striking about subject role shift in Mandarin is that while there is a special group of dual-subject EPs which may predicate either an Experiencer or a Stimulus, in a formally unmarked, non-derived way. For example, the intransitive predicate 無聊 wuliao (“be boring or bored”) may be used alternatively with an Experiencer or Stimulus without formal changes. Thus, the sentence below is potentially ambiguous, meaning either “He is bored” or “He is boring”:

-

(30)

Dual meanings with intransitive verb 無聊 wuliao

-

他很無聊

ta__hen__wuliao

3p.sg__DEG__bored/boring

a. He is bored.→ Experiencer as subject

b. He is boring.→ Stimulus as subject

-

Given the dual subjecthood, 無聊 wuliao may still be used in the above-mentioned causative pattern as other Experiencer-subject EPs, to highlight a Stimulus-causer, as in 這本書令人無聊 zhe-ben shu ling-ren-wuliao [CAU-person-bored] “The book is boring.”

Another dual-subject verb 討厭 taoyan “detest/loathsome” predicates a Stimulus in its intransitive use, but an Experiencer in its transitive use. Like other dual-subject EPs, it may also be used in the productive causative pattern. Thus, the verb may alternate in three different constructions:

-

(31)

Three-way alternation with 討厭 taoyan “detest/be detestable”

-

a.

Stimulus-Intransitive

這本書很討厭

[zhe-ben__shu]Stim__hen__taoyan.

this-CL__book__DEG__detestable

This book is annoying/detestable.

-

b.

Experiencer-Transitive

我很討厭這本書

[wo]Exp__hen__taoyan__zhe-ben__shu..

1p.sg__DEG__detest__this-CL__book

I dislike this book.

-

c.

Stimulus-Causative

這本書讓我很討厭

[zhe-ben__shu]Stim__rang__wo__hen__taoyan.

this-CL__book__CAU__1p.sg__DEG__detest

The book makes me dislike it.

-

a.

There are other sets of dual-subject EPs that associate different subject roles with varied syntactic patterns. The verbs such as 委屈 weiqu “aggreive,” 困擾 kunrao “puzzle,” 感動 gandong “touch” predicate an Experiencer when used intransitively, but a Stimulus head when used transitively. As exemplified below, these verbs can participate in the Stative-Causative alternation and the Stimulus-subject transitive pattern, be it stative (with the degree marker hen) or eventive (with the perfective marker 了 le). All together, they may participate in a four-way constructional alternation: the stative intransitive 32a, the stative causative 32b, the stative transitive 32c, and the eventive transitive 32d:

-

(32)

Four-way alternation with dual-subject predicates:

-

a.

Intransitive with Experiencer-subject

他很委屈/困擾/感動

ta__hen__weiqu/kunrao/gandong.

3p.sg__DEG__aggrieved/confused/touched

He’s aggrieved/confused/contented/touched.

-

b.

Causative with Stimulus-subject

這件事讓他很委屈/困擾/感動

zhe-jian__shi__rang__ta__hen__weiqu/kunrao/gandong.

this-CL__matter__CAU__3p.sg__DEG__aggrieved/confused/touched

This matter makes him aggrieved/confused/touched.

-

c.

Stative transitive with Stimulus-subject

這件事很委屈/困擾/感動他

zhe-jian__shi__hen__weiqu/kunrao/gandong__ta

this-CL__matter__DEG__aggrieve/confuse/touch__3p.sg

This matter fairly aggrieves/confuses/touches him.

-

d.

Eventive transitive with Stimulus-subject

這件事委屈/困擾/感動了他

zhe-jian__shi__weiqu/kunrao/gandong__le__ta

this-CL__matter__aggrieve/confuse/touch__LE__3p.sg

This matter aggrieved/confused/touched him.

-

a.

The abovementioned verbs are semantically and syntactically diverse, challenging the traditional lexical divisions based on semantic roles and argument expressions. What is of particular interest here is that the dual-subject verbs are able to predicate both Experiencer and Stimulus, breaking down the basic line between Experiencer-subject vs. Stimulus-subject verb classification.

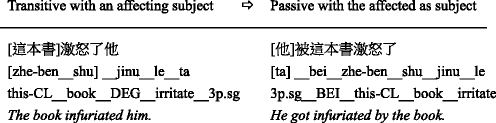

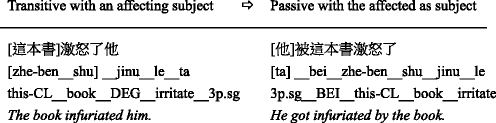

Moreover, the rather static notions of Stimulus and Experiencer may not be adequate to describe the relation implicated in the distinct group of EPs in the form of V-R compounds, e.g., 激怒 jinu “infuriate, irritate,” 惹火 rehuo “enrage, anger,” and 惹惱 renao “anger, exasperat.” These verbs imply an attainable result by the R-component with high affectedness. As already shown above, they are not readily compatible with degree evaluation and prefer to take on the eventive marker 了 le. A further constructional contrast with their passive use can also help to indicate their distinct lexical status. When these verbs are used in a passive construction, with the typical passive marker 被 bei, they rarely allow the addition of degree modification, while verbs that may denote either a stative or eventive meaning, such as 吸引 xiyin “attract” and 刺激 ciji “stimulate”, may optionally take the degree modifier 很 hen, as shown below:

-

(33)

Stative Transitive-Passive alternation: compatible with 很 hen

-

(34)

Eventive Transitive-Passive alternation: incompatible with 很 hen

The distinction with degree modification in the passive constructions, pertaining also to the stative-eventive distinction, can be compared with the adjectival vs. verbal passive distinction in English (with-pp vs. by-pp), as illustrated in 4 above. In English, the semantic distinction is not clear in the active voice but may be syntactically surfaced in the passive version with different prepositions. The verbal passive (with by-PP) may convey a similar function as the Mandarin eventive passive, which signals a more affective relation between the subject and object. This leads to the postulation of a different set of semantic roles, Affector and Affectee, in the next section.

Constructional alternations with subject role shifts bear significant consequences in determining the lexical classes of the predicates. Besides the small group of Stimulus-subject intransitive predicates (e.g., 枯燥 kuzao “dull,” 恐怖 kongbu “horrible” in 20a) that can only be used in the stative intransitive construction without role shifting, we’ve seen six types of predicates that allow a subject-role shift, each associated with a distinct set of constructional alternations:

-

(35)

Six types of role-shifting emotional predicates:

-

a.

verbs with the Stative-Causative alternation as in 29:

lexically specified with an Experiencer-subject:

-

b.

verbs with the Experiencer-Stimulus alternation, as in 30

lexically dual-headed with intransitive Experiencer or Stimulus

-

c.

verbs with the three-way alternation, as in 31

lexically dual-headed with intransitive Stimulus or transitive Experiencer

-

d.

verbs with the four-way alternation, as in 32:

lexically dual-headed with intransitive Experiencer or transitive Stimulus

-

e.

verbs with the stative Transitive-Passive alternations, as 33:

lexically specified with a transitive Stimulus

-

f.

verbs with the eventive Transitive-Passive alternation only, as in 34:

lexically specified with an affecting subject and an attainable result

-

a.

A finer distinction of the semantic roles of the subject is necessary, as proposed below, to help differentiate the observed variations in the subclasses.

3.4 Distinction of thematic roles: Stimulus-Experiencer vs. Affector-Affectee

The fact that a causative structure is called upon to express a Stimulus-subject relation suggests that the role of a Stimulus is taken to be functionally identical to a Causer. This has been mentioned to confirm what Pesetsky (1995: 56) proposed regarding the hierarchy of assigning thematic roles to subjecthood: Causer > Experiencer > Target/Subject matter. The hierarchy helps to point out the essential role of a Causer in emotional predication. When a Stimulus becomes the subject, its semantic function as a Causer is overtly expressed with the overtly marked causative construction in Mandarin. This syntactic strategy with constructional shift strongly suggests that the relation from Stimulus to Experiencer is fundamentally causal.

On the other hand, verbs that participate in the Transitive-Passive alternation are presumably associated with an agent-patient relation or a cluster of Proto-Agent vs. Proto-Patient features (cf. Dowty 1991). As illustrated above, some of these verbs are more stative and compatible with a degree modifier (e.g., 吸引 xiyin “attract” as in 33), but the others are inherently eventive (e.g., 激怒 jinu “infuriate, irritate” as in 34), showing a higher degree of volitionality, telicity, punctuality, control, and dynamic aspectuality, which together indicate higher transitivity (cf. Hopper and Thompson 1984). The following is a comparison of the two types of transitive verbs: the more eventive 激怒 jinu “infuriate” vs. the more stative 吸引 xiyin “attract”:

-

(36)

Features with higher eventivity and agentivity:

-

a.

Volition (with adverbial 故意 guyi “deliberately”):

他故意激怒/?吸引我

ta__guyi__jinu/?xiyin__wo.

3p.sg__deliberately__irritate/?attract__1p.sg

He deliberately infuriated/?attracted me.

-

b.

Telicity/boundedness (with perfective 了 le and frequency 兩次 liangci “twice”):

他激怒/?吸引了我兩次

ta__jinu/?xiyin__le__wo__liangci.

3p.sg__irritate/?attract__LE__1p.sg__twice

He infuriated/?attracted me twice.

-

c.

Punctuality (with adverb of immediacy 一下子 yixiazi “instantly”):

他一下子就激怒/?吸引了我

ta__yixiazi__jiu__jinu/?xiyin__le__wo.

3p.sg__instantly__irritate/?attract__1p.sg

He infuriated/?attracted me in no time.

-

d.

Control (with imperative/prohibitive):

別激怒/?吸引我

bie__jinu/?xiyin__wo!

don’t__irritate/?attract__1p.sg.

Don’t infuriate/?attract me.

-

e.

Dynamic process (with progressive 在 zai):

他在激怒/吸引我

ta__zai__jinu/?xiyin__wo

3p.sg__ASP__irritate/?attract__1p.sg

He is infuriating/?attracting me.

-

a.

In view of the comparison, we see that finer distinctions of affectedness in terms of realization of change (Beavers 2011, 2013) may be both lexically and grammatically differentiated. Examples with 激怒 jinu “infuriate” apparently allow the subject to exercise more control over the directly affected object. The semantic distinction, as mentioned previously, is referred to by Jackendoff (1991:140) as the stative vs. eventive distinction on Stimulus-subject verbs, and noted in Levin (1993: 191) as agentive vs. non-agentive role distinction. Dowty (1991: 580) attributed the inchoative (his term for “eventive”) use to the entailment of the Proto-Patient property in the object, reminiscent of the accusative marking of Experiencer in the Czech data. In Mandarin, there is even a stronger correlation of the semantic distinction with formal differentiations. The highly change-entailing verbs (e.g., 激怒 jinu “infuriate”) are morphologically distinct as V-R compounds and syntactically distinct in taking dynamic aspectual markers (perfective 了 le or progressive 在 zai). They lexically encode a “change of state” that is morphologically attained with the second component in the sequence of V-R, literally combining an active verb 激 ji “stir” and a resultative 怒 nu “angry” (lit. “stir-anger”).

The entailed “change of state” in the V-R verbs also enables them to occur in the cardinal transitive 把 ba-construction, which profiles a bounded event with an attainable result or extent (c.f. Hopper and Thompson 1984). It is found that the more impact-assuring a verb is, the more likely it is to participate in this highly transitive 把 ba-construction. In the following examples, we see a clear difference between impactive V-R verbs (激怒 jinu “stir-angry” and 惹惱 renao “cause-upset”) and the others:

-

(37)

Occurrence with 把 ba-construction:

他把我激怒/惹火/?吸引/?刺激了

ta__ba__wo__jinu/rehuo/?xiyin/?ciji__le.

3p.sg__BA__1p.sg__irritated/infuriated/?attracted/?stimulated__LE

He has (surely) infuriated/angered/#attracted/#stimulated me.

This distributional difference may add to the evidences that point to a finer distinction of semantic relations. The Mandarin grammar makes it clear that the agentive vs. non-agentive subject roles and the stative vs. eventive predications are lexically and constructionally distinct and may constitute distinct subclasses in the lexicon.

In view of the above distinctions, a separate thematic role for the subject is proposed. It is named “the Affector,” a term inspired by the notion of Effector in Van Valin and Wilkins (1996), referring to a “dynamic participant doing something in the event.” The Effector is quasi-agentive, functioning as an “instigator” or the first CAUSE in a causal sequence. It is argued that Effector is a more basic function underlying similar roles of agent, force, and instrument. Applying the notion of Effector to emotional predication, which involves internal, affective impact, the term Affector is chosen to highlight the affective change it instigates. It can be defined as a dynamic participant doing something for an affective impact on a sentient patient-like goal, the Affectee. The thematic relation between Affector and Affectee is semantically and syntactically distinct from that of Stimulus and Experiencer. It is thus recognized as an alternative way of conceptualizing the causal schema in emotional predication, profiling a more dynamic impact between an affecting force and an affected participant. At the conceptual level, the two thematic relations, Affector-to-Affectee vs. Stimulus-to-Experiencer, can both be mapped unto the proto-schema of causal chain underlying emotional predication, as represented below:

-

(38)

Conceptual schema for stative vs. eventive thematic relations:

The two sets of thematic relations distinguished here represent two alternative ways of conceptualizing and encoding emotional affect. They correspond to two different event types, manifesting the stative vs. eventive distinction. The eventive type, previously taken to be implicit in Stimulus-subject verbs, is now distinguished and labeled with a distinct set of roles, Affector to Affectee. According to Dowty (1991), the identification of “legitimate” kinds of thematic roles should follow at least two criteria: it should be event-dependent, not just perspective-dependent; and it should be relevant to argument selection. In view of the two criteria, the postulation of an Affector, as distinct from a Stimulus, is well-motivated since it indeed correlates to a distinction in event type and argument realization. In the sentence below, Affector can be conceived as a separate argument, which exerts an impact on the Affectee by means of a Stimulus:

-

(39)

老師[Affector]用話[Stimulus]激怒了學生[Affectee]

laoshi [Affector]__yong__hua [Stimulus]__jinu__le__xuesheng[Affectee]

teacher__by__words__irritate__LE__student

The teacher [Affector] angered the students [Affectee] with his words [Stimulus].

As evidenced above, the role Affector can be separated from the Stimulus as they may co-occur in the same sentence. The different thematic relations represented above are typically associated with different constructional alternations: Stimulus-Experiencer with the stative-causative alternation, while Affector-Affectee, with Inchoative, Passive, and Ba-constructions:

-

(40)

Constructional alternations typically associated with different thematic frames:

-

a.

<Stimulus, Experiencer>: Stative-Causative alternation

-

Stative:

我[Exp]很擔心他

wo[Exp]__hen__danxin__ta

1p.sg__DEG__worry__3p.sg

I am worried about him.

-

Causative:

他[Exp]讓我很擔心

ta[Stim] __rang__wo__hen__danxin

3p.sg__CAUS__1p.sg__DEG__worry

He made me worried (about him).

-

Stative:

-

b.

<Affector, Affectee>: Inchoative, Passive, and ba-construction

-

Inchoative:

他的話激怒了我

tade__hua[Affector] __jinu__le__wo[Affectee]

his__words__infuriate__LE__1p.sg

His words infuriated me.

-

Passive:

我被他的話激怒了

wo[Affectee]__bei__tade__hua__jinu__le

1p.sg__BEI__his__words__anger__LE

I got infuriated by his words.

-

ba-construction:

他的話[Affector]把我激怒了

tade__hua[Affector] __ba__wo__jinu__le

his__words__BA__1sg__infuriate__LE

His words got me infuriated. (highly transitive)

-

Inchoative:

-

a.

Besides morphological cues, the formal variation in constructional association provides further evidence for the distinction of semantic relations. Another piece of evidence supporting the postulation of the Affector-Affectee relation comes from the account of excessive predication in Liu and Hu (2013). The study examines the form-meaning mismatch found only in emotional expressions with an excessive marker, such as 死 si “excessively” (lit. “die”), whereby a switch of arguments in grammatical positions does not seem to render a corresponding switch of meaning. The two sentences below with a mere positional swap of subject and object do not seem to change their respective roles (ibid.: 51-52):

-

(41) a.

我羨慕死他的好運了

wo__xianmu__si__tade__hao-yun__le

1p.sg__envy__die__his__good-luck__LE

I envy his good luck to death.

-

b.

他的好運羨慕死我了

tade__hao-yun__xianmu__si__wo__le

his__good-luck__envy__die__1p.sg__LE

His good luck made me envious to death.

Notice that although the second sentence is translated as an English causative, there is no causative marking involved in the Chinese sentence. The only formal difference is the mere positional swap of the two arguments involved. While a formal change is normally accompanied by a semantic change, it is puzzling why the shifted arguments maintain the same semantic functions (Liu and Hu 2013:52):

-

(42)

Positional shift between owner-of-emotion and target-of-emotion: