- Original Article

- Open access

- Published:

Modality and aspect and the thematic role of the subject in Late Archaic and Han period Chinese: obligation and necessity

Lingua Sinica volume 3, Article number: 10 (2017)

Abstract

In this paper, the interplay of modal markers with the lexical aspect of the verb in Han period Chinese is at issue. Abraham and Leiss (Modality-aspect interfaces: Implications and typological solutions, 2008) propose a strong and possibly universal relation between the verbal aspect and either the root/deontic or the epistemic reading of a modal verb based on data from the Germanic languages. In this article, this hypothesis will be checked against the data of Late Archaic and Early Middle (Han period) Chinese. It will be proposed that a relation similar to that in the Germanic languages can also be established for Chinese at least for the root modal values, despite the obvious differences between the aspectual and modal system of Chinese and that of the Germanic languages. As in the Germanic languages, root modal verbs in general select verbs/predicates which are compatible with the perfective aspect, i.e. [+TELIC] verbs. Due to the fact that epistemic readings have not developed yet for modal auxiliary verbs, the constraints proposed in Abraham and Leiss for the epistemic reading of modal verbs in combination with imperfective or [−TELIC] verbs cannot be confirmed for LAC and EMC. Epistemic modality is expressed by sentential adverbs which take an entire proposition as their complement. These are less confined in their selectional restrictions than modal auxiliary verbs.

1 Background

In this paper, the AM (aspect-modality) system in Late Archaic (fifth–second c. BCE) and Early Middle (first c. BCE–sixth c. CE), specifically in Han period Chinese (206 BCE–220 CE), will be discussed. The paper proposes a strong relation between root modal markers and the lexical [+TELIC/TERMINATIVE] aspectual features of the embedded VP (verb phrase) in LAC (Late Archaic Chinese) and EMC (Early Middle Chinese); thus, it provides some evidence for the hypothesis on universal relations between aspect and modality proposed in Abraham and Leiss (2008).Footnote 1 In an earlier paper, Meisterernst (2016a) argued that aspectual distinctions in LAC rather concern the lexical than the grammatical aspect. Accordingly, the present discussion focusses on the relation between the lexical aspect and modal readings in LAC and EMC.

The system of modal markers and its diachronic development in Chinese has continually gained more interest in the linguistic literature (see Li 李明 2001; Liu 刘利 2000; Meisterernst 2008a, 2008b, 2011; Peyraube 1999 for LAC and for diachronic studies, and e.g. Alleton 1984; Li 2004 for Modern Chinese). The same holds true for the diachronic development of the aspectual system, i.e. the development of the source structures of the aspectual markers of Modern Mandarin on the one hand, and for the constraints, the lexical aspect imposes on the employment of aspectual markers not only in modern but also in LAC and Han Chinese on the other (Aldridge and Meisterernst 2017; Cao 曹广顺 1999; Jiang 蒋绍愚 2001, 2007; Jin 金理新 2006; Mei 梅祖麟 1980; Meisterernst 2015a, 2016b). However, systematic relations between modality and aspect, which according to Abraham and Leiss (2008) are frequently not even established in well-studied languages, have hitherto not found much interest in diachronic and synchronic studies of Chinese. The present paper focuses on the system of aspect and modality in LAC and Early Middle (Han period) Chinese, one of the important transition periods of Chinese, in order to establish the basic constraints of the interplay between aspect and modality in pre-Modern Chinese. The paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, the theoretical background and the diachronic development of aspectual and modal features in Chinese will be discussed. In Section 3, the proposed hypothesis will be checked against the root modal verbs of Late Archaic and Han period Chinese; in Section 4, the conclusions drawn from the discussion will be presented.

2 An introduction to aspect and modality

2.1 The interrelation of aspect and modality

In this section, the theoretical background of the discussion as it has been proposed in Abraham and Leiss (2008) will be introduced. Abraham (1991) observes dependencies between the reading of a modal verb and the aspectual features of the embedded infinitival complement in the Germanic languages:

‘- modals combine with lexically perfective infinitives in order to generate deontic meaning (DMV)

- modals combine with imperfective infinitives in order to generate epistemic meaning (EMV)

-

(1)

a. He must leave now. (DMV/*EMV) ≠

b. He must be leaving now. (*DMV/EMV)

c. He must give money to them. (DMV/*EMV) ≠

d. He must be giving money to them. (*DMV/EMV) (Leiss 2008: 17)

This observation among others results in Abraham’s and Leiss’ proposal (2008: xiii) that

-

Perfective aspect is compatible (‘converges strongly’) with root modality

-

Imperfective aspect is compatible (‘converges strongly’) with epistemic modality.Footnote 2

-

Negated clauses as a rule select imperfective aspect only, without necessarily yielding epistemic modality.

This classification accounts for the fact that root modals, i.e. deontic modals in a wider sense, take an event as their complement, whereas epistemic modals take a proposition as their complement: root modals are event modifiers (Abraham and Leiss 2008: xx). This has been evidenced by Abraham (2009: 265) with German modal verbs for which epistemic readings are difficult to obtain with telic [+TERMINATIVE] verbs, whereas both deontic and epistemic interpretations are possible with atelic [−TERMINATIVE] verbs. The feature [+/−TERMINATIVE] rather refers to aktionsart features, i.e. the lexical aspect of the verb/predicate, than to the grammatical, i.e. the perfective and the imperfective aspect of the VP.Footnote 3 Lexical aspect is characterized by the semantic feature of telicity or boundedness which refers to the natural initial and final points of a situation. States and activities are atelic or unbounded (non-terminative in Abraham’s terminology), neither the initial nor the final points of the situation are included in their temporal structure; they are monophasic (Abraham and Leiss 2008: xiv). Events (accomplishments and achievements) are telic (terminative according to Abraham): achievements merely include the final change of state point, accomplishments also include the process part of the situation; they are biphasic (Abraham and Leiss 2008).Footnote 4 Atelic predicates are compatible with duration phrases, for x time, whereas telic predicates are compatible with time span adverbials in x time. The structure of the lexical aspect (Aktionsart) is compositional; it can consist of a single verb, but also of complex VPs, including V-O phrases and V-(O)-PP phrases, which contribute to the overall aspectual structure of a particular sentence.Footnote 5 The following example from Travis (2010: 246) represents a typical aspectual shift from telic to atelic due to the characteristics of the complement(s) of the verb push. The predicate push the cart is atelic, and no endpoint is indicated in the temporal structure of the predicate. In 2b, an endpoint is added by the prepositional phrase to the wall, and because the event measuring DP in 2c is a bare plural, it changes the entire situation back to a [−telic] situation.

-

(2)

a. push DP sg –atelic

The children pushed the cart. (*in three minutes/√for three minutes)

b. push DP sg PP–telic

The children pushed the cart to the wall. (√in three minutes/*for three minutes)

c. push DP barepl PP–atelic

The children pushed carts to the wall. (*in three minutes/√for three minutes)

-

(3)

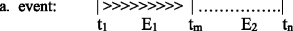

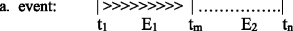

The temporal structure of terminative, i.e. telic situations according to Abraham and Leiss (2008: xiv), i.e. the structure of verbs such as ‘die’ and ‘kill’:

In this representation, t1 refers to the initial point of the approach/incremental phase E1; the point tm refers to the initial point of the second, the resultative phase E2; tn refers to a final point of the situation. The point tm belongs to both phases. This structure accounts, e.g. for the LAC achievement verb 死 sǐ ‘die’ in example 4a which refers to E2 and to the accomplishment verb 築 zhú in 4b which can refer to E1 and E2 depending on the grammatical construction it appears in. One of the distinguishing features between these two categories is the role of the subject. Achievement verbs are usually considered to have a theme subject, and accomplishments have a causer or agent subject.Footnote 6 Note that neither of those constructions has to be marked for aspect by any overt morphological means.

Non-terminative monophasic verbs only consist of a process or state part: E1 and E2 are assumed to be identical. The structure of 3b1 accounts for non-terminative (−TELIC) (in)transitive verbs such as live and push, respectively (for push see example 2), 3b2 accounts for state verbs such as 高 gāo ‘high’ in LAC and EMCFootnote 7 in example 4c.

-

(4)

Examples for the [+/−TELIC] predicates in early MC:

-

a.

襄王母蚤死, 後母曰惠后. [+TELIC] (史記 shǐjì ‘Records of the Grand Historian’: 4; 152)

xiāng__wáng__mŭ__zǎo__sĭ__hòu__mŭ__yuē__huì__hòu

Xiang__king__mother__early__die__later__mother__say__Hui__hou

King Xiang’s mother died early and the later (step) mother’s name was Hui hou.

-

b.

燕亦築長城, 自造陽至襄平. [+TELIC] (Shǐjì: 110; 2886)

yān__yì__zhú__cháng__chéng,__zì__zàoyáng__zhì__xiāngpíng

Yan__also__build__long__Wall,__from__Zaoyang__to__Xiangping

Yan also built a great Wall from Zaoyang to Xiangping.

-

c.

平定天下, 為漢太祖, 功最高. [−TELIC] (Shǐjǐ: 8; 392)

píng__dìng__tiānxià,__wéi__hàn__tàizŭ,__gōng__zuì__gāo

peaceful__settle__empire,__be__Han__ancestor,__merit__very__high

… he has settled the empire in peace, and has become the honoured ancestor of the Han and his merits are most high.

In general, events (accomplishments and achievements) focusing on either t1 or tm are compatible with the perfective aspect; states and activities focusing on neither of the final points of a situation are compatible with the imperfective aspect. The interplay of the verb and its arguments, and additionally the employment of adverbs which can e.g. express perfective and imperfective meanings play an important role in the determination of the lexical aspect and in aspectual shifts in Han period Chinese.Footnote 8

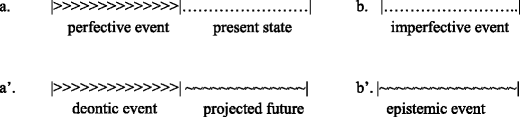

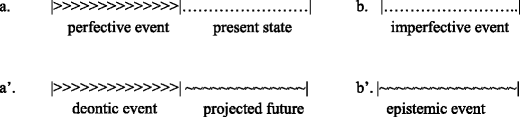

For the reading of modal verbs, Abraham proposes a structure similar to that of telic (perfective) and atelic (imperfective) verbs. According to him deontic events are bi- phasic, corresponding to [+TELIC/TERMINATIVE] events, and epistemic events are monophasic corresponding to [−TELIC/TERMINATIVE] events. These structures are summarized in Leiss (2008: 17) in the following way:

-

(5)

Biphasic deontic and monophasic epistemic events

In the perfective event, the incremental phase E1 corresponds to the deontic event; the resultant state E2 corresponds to the projected (resultative) future event. In epistemic events just as well as in imperfective events, this distinction into two separate phases cannot be observed.

Abraham and Leiss base the hypothesis of a close relation between deontic modals and biphasic events on the diachronic development of the modal system in the Germanic languages. The Germanic languages developed a particularly articulate class of modal verbs within the Indo-European languages (see Abraham and Leiss 2008 and references therein). Diachronically the development of the class of modal verbs has been connected to the loss of an earlier aspectual system in the Germanic languages (Leiss 2008): “Languages which have lost an elaborate aspect system tend to develop articles … as well as a class of modals with deontic and epistemic meanings ....” Germanic modal verbs start to grammaticalize from preterite-presents, and, even more importantly for the present discussion, they tend to embed a perfective infinitive (see Leiss 2008: 18).Footnote 9 The feature of perfectivity always includes the future-projecting features typical for deontic modals (Leiss 2008: 19). Two examples from Old English (OE) and from Old High German (OHG) with deontic modals selecting perfective infinitives demonstrate this relation (from Leiss 2008: 26). The infinitive is marked as perfective (resultative) by the prefix ge-.Footnote 10

-

(6)

a. OE thaet__ic__saenaessas__ge-seon__mihte

that__I__sea-bluffs__see__[pf-see]__might

So that I could see the cliffs (Beowulf 571)

b. OHG uuer__mag__thaz__gi-horen who

can__that__hear__[pf-hear]

Who can understand that? (Tatian (Masser-edition). 263, 30)

The precise function and the status of this prefix as expressing either aktionsart or perfective aspect are subject to debate (see Besch et al. 2003: 2520; Vogel 1995: 178). The employment of the Germanic aspectual suffix seems to be less obligatory than the systematic and obligatory marking of the perfective and the imperfective aspect in the Slavic languages (Dal and Eroms 2014: §78). Nevertheless, there are some arguments in favour of the hypothesis that Old Germanic had a grammatical aspectual system (Besch et al. 2003), although it cannot be entirely excluded that an analysis of ge- as marker of the lexical aspect (situation type) is more conclusive. Aktionsart morphology is derivational in nature and can be marked or unmarked,Footnote 11 whereas the viewpoint aspect has to be marked obligatorily in languages with a grammaticalized perfective-imperfective distinction. When the Germanic languages lose the former category of aspect (especially the perfective ge-verbs), they start to develop an elaborate class of deontic and epistemic modal verbs. Modal distinctions had previously been expressed by the interplay of aspectual and temporal marking alone. The diachronic development in the Germanic languages in contrast to other IE languages obviously points to a close and possibly universal relationship between the categories aspect (lexical and/or grammatical aspect) and modality.

The hypotheses on the interplay of aspect and modality presented above are according to Abraham not unchallenged and emerge most obviously from the German data (Abraham and Leiss 2008: xxii). Nevertheless, they will be taken as a point of departure in this paper for the analysis of the Chinese data despite the differences between the aspectual and modal system of Chinese and that of the languages studied in Abraham and Leiss.

2.2 Aspect in Han period Chinese

Chinese is a member of the Sino-Tibetan/Tibeto-BurmanFootnote 12 language family. The earliest stages of the Tibeto-Burman languages have been reconstructed as monosyllabic with some derivational affixes (LaPolla 2003: 22); they did not have an inflectional morphology comparable to that of the IE languages. As can be seen, e.g. in Written Tibetan and in Burmese, the Sino-Tibetan derivational morphology includes aspectual distinctions within the verbal system. Due to its particular writing system which tends to obfuscate phonological differences, the Chinese language has often been labelled as an isolating language entirely lacking any morphological distinctions. But studies on the historical phonology of Chinese demonstrate that Chinese must have had a kind of morphology by affixation comparable to that of related languages such as Tibetan or Burmese. Different affixes affecting the verbal system have been reconstructed based on evidence from early Chinese sources such as dictionaries, rime books, rime tables, transcriptions of foreign words, and more recently also on dialectal evidence and on comparative studies. In Chinese, this morphology disappeared much earlier than in, e.g. Tibetan and Burmese; it had been entirely lost at the time of the earliest Tibetan written documents (seventh c. CE). According to Schuessler (2007: 41), even one of the youngest derivational morphemes, i.e. the suffix *-s, proposed in the literature (e.g. Jin 金理新 2006) as marker of the perfective aspect, had “become a general purpose device to derive any kind of word from another” in Archaic Chinese.Footnote 13 In the LAC period, this morphology was certainly not productive anymore, and by the end of the LAC period (third–second c. BCE), the functions of its vestiges probably ceased to be transparent for the speakers of the time. The verbal morphology reconstructed for Archaic Chinese usually proposes distinctions within the category aspect, i.e. the perfective and the imperfective aspect, a distinction between transitive and intransitive verbs and/or causative and unaccusative verbs (see, e.g. Jin 金理新 2006). In Meisterernst (2016b), it has been argued that the aspectual distinctions expressed by the reconstructed verbal morphology rather concern the lexical than the grammatical aspect. The lexical aspect, aktionsart, is generally derived by derivational morphology (Kiefer 2010: 145), the kind of morphology proposed as typical for the Tibeto-Burman languages. The aktionsart morphology adds semantic features to the verb such as ingressivity, terminativity and iterativity. (Kiefer 2010). This fits well the meanings proposed for a number of derivational affixes reconstructed, e.g. in Sagart (1999).Footnote 14 Two different derivational processes have been proposed for the distinction of verbal aspects (e.g. Huang 黃坤堯 1992; Jin 金理新 2006; Unger 1983):

-

a)

The suffix *-s indicating the perfective aspect (Downer 1959; Jin 金理新 2006; Haudricourt 1954a, 1954b; Sagart 1999; Unger 1983; etc.); or

-

b)

A voiceless (imperfective)–voiced (perfective) alternation of the root initial possibly caused by a former sonorant nasal prefix (Baxter and Sagart 1998; Karlgren 1933; Mei 梅祖麟 1988; etc.) or by the causative prefix *s-.

The first of these processes, the 四聲別意 sì shēng bié yì ‘derivation by tone change’ (e.g. Sagart 1999: 131), is the most prominent and most widely accepted derivational process of Archaic Chinese. It is attested with words of any of the tonal categories A (平 píng), B (上 shǎng), and D (入 rù), which are transformed into category C (去 qù).

The category C is supposed to have developed from a former derivational suffix *-s which changed into -h and further into the 去聲 qùshēng.Footnote 15 This process most likely took place at the end of the LAC and in the EMC periods; the differences in pronunciation resulting from it are, e.g. reflected in the 反切 fǎnqiè glosses to the Classics from the Han period on.Footnote 16 Double readings and minimal pairs with readings in one of the mentioned categories and in category C are relatively frequent.Footnote 17 Jin proposes basically two different functions of the suffix *-s (e.g. 2006: 317, 321, 325f): a transitivization function and a deverbalization function (2006: 325). For the latter he claims that the change from verb to noun can often be subsumed under a change from the imperfective to the perfective aspect (Jin 金理新 2006).Footnote 18 The suffix (OC *-s, *-h) is probably related to the Tibeto-Burman suffix –s (Huang 黃坤堯 1992; Jin 金理新 2006; Schuessler 2007: 42; etc.); this was the most productive derivational affix in the Classical Tibetan language and obviously had aspectual functions.Footnote 19 An alternation between a category A and a category C reading is represented by example 7 from LAC. The qùshēng reading in 7b, which at the time had been in the process of developing from a former *-s/*h suffix, evidently refers to an achievement and the state resultant from a preceding telic event, and the reading in 7a is transitive and causative.

-

(7)

a. 政以治民, 刑以正邪。 (左傳 zuŏzhuàn 'Commentary of Zhuo', 隱公十一年 Yǐn 11)

zhèng__yǐ__chí__(*r-de (*drɨ)Footnote 20)__mín,__xíng__yǐ__zhèng__xié

Government__YI__regulate__people,__punishment__YI__correct__bad

The government is necessary in order to correct the people, the punishments are necessary to correct the bad.

b. … 使為左師以聽政, 於是宋治。 (Zuŏzhuàn, 僖公九年 Xī 9)

shǐ__wéi__zuǒshī__yǐ__tīngzhèng,__yúshì__Sòng__zhì__(*r-de-s (drɨh))

Cause__become__zuoshi__CON__manage-government,__thereupon__Song ordered

… he made him Zuoshi and let him manage the government, and thereupon Song was well ordered.

Another form of derivation is the 清濁別意 qīng zhuó bié yì ‘derivation by a voicing alternation’, an alternation of a voiced and a voiceless initial with functions similar to the derivation by tone change. The voicing alternation is reflected by tonal differences and/or by differences in the initial consonant in Modern Mandarin. Baxter (2000: 218; following Pulleyblank 1973) attributes the voicing effect to a pre-initial element *ɦ- provisionally reconstructed for words with a cognate with a voiceless initial. Mei (2015) on the other hand proposes that a causative prefix *s- is responsible for a devoicing effect on an originally voiced initial. A causative prefix *s- has been reconstructed for Archaic Chinese, and it is also well attested in Classical Tibetan (and other Tibeto- Burman languages) together with a voicing alternation. Pulleyblank’s and Baxter’s proposal is more likely, since it explains the fact that the unaccusative variant always begins with a voiced consonant (Aldridge and Meisterernst 2017, Aldridge personal communication). This alternation of voiced voiceless initials had already been connected to different verbal functions ‘intransitive/passive–transitive’ in the Jīngdiǎn shìwén (6th c. CE); the proposed functions are similar to the aspectual alternations assumed for the more frequent reconstructed suffix *-s, the source of the ‘derivation by tone change’.Footnote 21 Example 8 represents the voicing alternative with the verb 敗 bài ‘defeated, defeat’, one of the verbs discussed, e.g. in Mei (2015). This example displays the same alternation between an unaccusative and a causative variant of the verb as the verb in example 7. The voiced variant is unaccusative, characterized by a theme subject; unaccusative verbs are typical telic (achievement) verbs compatible with the perfective aspect. The voiceless variant is transitive and causative.

-

(8)

a. 蔡人怒, 故不和而敗。 (Zuŏzhuàn, 隱公十年 Yǐn 10)

cài__rén__nù,__gù__bù__hé__ér__bài (*blad-s, ɦprats)Footnote 22

Cai__man__angry,__there__NEG__harmonize__CON__defeated

The people of Cai were angry, and therefore they were not in harmony and were defeated.

b. 惠公之季年, 敗宋師于黃。(Zuŏzhuàn, 隱公一年 Yǐn 1)

huì__gōng__jì__nián,__bài (*plad-s, prats)__sòng__shī__yú__huáng

Hui__duke__SUB__last__year,__defeat__Song__army__at__Huang In the last year of Duke Hui he defeated the Song army at Huang. (see also Jin 金理新 2006: 83)

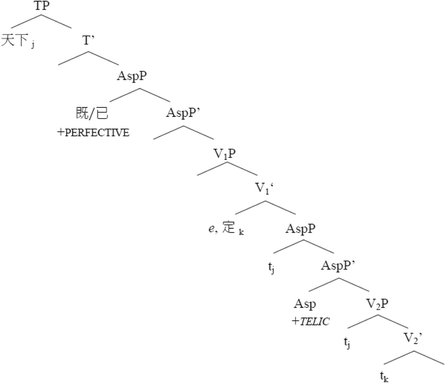

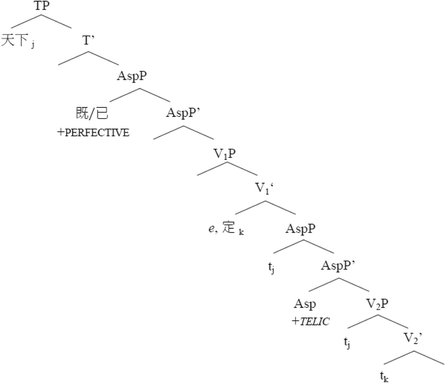

The examples demonstrate that according to the reconstructions based on reading variants reported in traditional Chinese lexicography Archaic Chinese might have had several different affixes expressing aspectual variations and related meanings. These are (a) the (more frequent and) generally accepted suffix *-s and (b) a sonorant prefix, reconstructed, e.g. as *ɦ-, deriving the unaccusative, resultative variant from a transitive variant (Baxter 2000; Pulleyblank 1973) (and/or a causative prefix *s-, deriving a causative variant from an unaccusative variant (Mei 2015)). Analyses of the morphology of a large number of representative verbs (for instance in Jin 金理新 2006) provide strong evidence for a morphological differentiation of different verbal aspects, or rather of activity and accomplishment verbs on the one hand and (resultant) states on the other.Footnote 23 This distinction based on telicity features provides an argument for a localization of the aspectual morphology in an Inner Aspect Phrase within an articulated VP (vP), as proposed in Meisterernst (2016b) following Travis (2010).Footnote 24 Additionally, the aspectual morphology of many of the verbs discussed in Jin 金理新 (2006) shows a close relation with the internal argument of the verb. This also supports the hypothesis that it rather concerns the category lexical aspect, usually characterized by derivational morphology, and not the category grammatical aspect. This also accounts for the function of some of the other affixes reconstructed, e.g. in Sagart (1999). The abstract morpheme, which can phonologically be represented by the suffix *-s, or, possibly, by the voicing alternation, reconstructed to be caused by a sonorant prefix *ɦ-, may be labelled with the feature [+RESULT].Footnote 25Additional to the mentioned affixes a null morpheme referring to telicity features has to be assumed; different items, including the item zero ø, can be inserted due to phonological and other rules of the respective language.Footnote 26 Functionally, these derivational affixes show a close resemblance to the Germanic prefix ge−/ga-, for which similar functions have been proposed (see Section 2.1). However, the linguistic data attested does not show precisely how long and to which extent these morphological distinctions were productive. During the LAC period, this system had certainly not been productive any longer and started to lose its transparency. At that time, verbs without an overt resultative marker and verbs in the qùshēng reading can identically refer to non-resultative accomplishments. Schuessler (2007: 46) shows that a derived verb in the qùshēng could become an independent, e.g. transitive verb of its own accord.

The loss of the morphology of Archaic Chinese can serve as an explanation for the significant structural changes Chinese underwent from LAC to EMC, e.g. the change from a more synthetic to a more analytic language; this includes the emergence of light verbs, resultative constructions and disyllabification processes. (see e.g. Feng 2014; Hu 2016; Huang 2014; and others). In the aspectual system, distinctions are increasingly expressed by lexical means, i.e. by aspectual adverbs and possibly by sentence final particles, before a new structure for the marking of aspect develops in the EMC period.

From the end of the LAC period, the perfective adverbsFootnote 27 既 jì and 已 yǐ appear freely with both atelic and genuinely telic verbs. The atelic verbs are confined to stage-level predicates, i.e. predicates which allow a change of state reading. With state verbs, the adverbial modification induces an inchoative reading and with activity verbs the natural endpoint of the activity is focussed on (Meisterernst 2015a, 2016b). For the verb zhì 治 ‘govern(ed)’ in example 9, the morphological distinctions might still have been transparent at this time. Accordingly, the ratio of instances modified by an aspectual adverb is very low (less than 1% in LAC).Footnote 28 In 9a, a combination of the perfective adverbs 既 jì and 已 yǐ modifies the unaccusative variant 治 zhì; in 9b and 9c, a perfective adverb modifies transitive predicates with the verbs 治 zhì (chí) and 并 bìng ‘unify(ed)’, respectively. Since causative morphology is also probably generated in the Inner Aspect Phrase, causative examples like 9b and 9c provide an additional argument for the aktionsart hypothesis and the generation of the verbal morphology in an Inner Aspect Phrase (Meisterernst 2016b). Note that all examples are comparatively late. Example 9d represents the non-default employment of a perfective adverb with a state verbFootnote 29; modified by a perfective adverb a coercion effect is induced, the initial point of the state is focused leading to an inchoative reading (Meisterernst 2016b).

-

(9)

a. 許由曰:「子治天下, 天下既已治也。 (莊子 zhuāngzǐ ‘Zhuangzi’ 1.2.3, ca. 3rd c. BCE)

xǔ__yóu__yuē:__zǐ__chí(r-de)__tiānxià,__tiānxià__jì__yǐ__zhì(r-de-s)__yě

Xu__You__say:__You__regulate__empire,__empire__JI__YI__regulated__SFP Xu You said: “You regulate the empire, and the empire is already regulated.” (also Jin 2006: 322)

b. 季子曰:『堯固已治天下矣, (呂氏春秋 lǚshì chūnqiū ‘Lu’s Commentary of History’ 25.3.2.1, 3rd c. BCE)

jì__zǐ__yuē__yáo__gù__yǐ (chí (r-de))/zhì (r-de-s)__tiānxià yǐ

Jizi__say:__Yao__certainly__YI regulate__empire SFP

‘Jizi said: “Yao had certainly already regulated the empire.”’

c. 秦始皇既并天下而帝, 或曰: (Shǐjì: 28; 1366, late 2nd c. BCE)

qín__shĭ__huáng__jì__bìng__tiānxià__ér__dì,__huò__yuē

Qin__First__Emperor__already__unify__empire__CON__emperor,__someone__say

‘After the First Emperor of Qin had unified the empire and become emperor, someone said: …’

d. 成王在豐, 天下已安, 周之官政未次序. (Shǐjì: 33; 1522)

chéng__wáng__zài__fēng,__tiānxià__yĭ__ān,__zhōu__zhī__guān__zhèng__wèi__cìxù

Cheng__king__be-at__Feng,__empire__already__peace,__Zhou__GEN__office__government__NEGasp__regulate

‘King Cheng was in Feng, and the empire was already at peace, but the offices and the administration of Zhou had not been regulated yet.’

Both the grammatical and the lexical aspect convey information about the temporal structure of a situation and they are closely linked in a compatibility relation. The respective lexical aspect of the verb enhances or prevents a particular grammatical aspectual representation: telic verbs are generally compatible with the perfective aspect, and atelic (state and activity) verbs are generally compatible with the imperfective aspect. These default relations can be shifted by coercion effects from telic to atelic and vice versa when modified accordingly (Meisterernst 2015a, 2016b).Footnote 30

Another process which can be ascribed to the loss of morphology in LAC and EMC is the disyllabification process in Chinese together with the development of resultative constructions in EMC; some of the latter serve as the source structures of Modern Mandarin aspectual markers.Footnote 31In Modern Mandarin, the aspectual meaning of perfectivity can be expressed by the verbal suffix -le 了. Sybesma (1997, 1999) proposes an analysis of –le as denoting an endpoint or realization. Sybesma (1999: 72) treats LE as a ‘neutral telic marker’, and he analyzes both types of LE as small clause predicates. Sybesma (1994) proposes that the aspectual marker –le in Modern Mandarin and its diachronic development can actually be compared to the Germanic prefix ge-, which expressed completion in Middle Dutch (Sybesma 1994: 41). This claim supports the hypothesis proposed in this paper that a system of derivational affixes can be reconstructed for Archaic Chinese which displays functions comparable to those proposed for the Germanic aspectual prefix ge/ga-. The loss of the aspectual function of this prefix in Old German has been connected to the development of the German modal system; a similar process might also have taken place in EMC, i.e. in a language typologically entirely different from the Germanic languages. In Chinese, the complexity of the modal system only starts to increase in at the end of LAC, the time when the functions of the reconstructed affixes of Chinese started to lose their transparency. As in the early stages of the German language, modal verbs in LAC are to a considerable extent confined to different realizations of the ‘first modal’ (Leiss 2008: 16) ‘can’.Footnote 32 True deontic verbs only emerge in the EMC period, and the epistemic readings of modal verbs develop even later; this is the typical grammaticalization path for modal verbs. In LAC, epistemic modality is expressed by sentential adverbs; these have to be distinguished semantically and syntactically from modal verbs (Leiss 2008; Meisterernst 2016a). Sentential adverbs modify an entire proposition and are thus less confined in their constraints than modal auxiliary verbs; they are attested with both atelic and telic verbs.Footnote 33

2.3 Modality in Han period Chinese

In Han period Chinese, modal values are expressed either by auxiliary verbs or by adverbs. These two different categories cannot be distinguished morphologically, but to a certain extent syntactically; they differ for instance with regard to the position of negative markers and wh-words (Meisterernst 2013). Root and deontic values in a strict sense, having to do with laws, norms, etc., but also other non-epistemic values, are predominantly expressed by a closed class of modal auxiliary verbs. Epistemic values having to do with the knowledge or belief of the speaker are predominantly expressed by modal adverbs.Footnote 34 Adverbs which have an epistemic or ‘epistemic-like’ reading as their predominant reading are, e.g. 必 bì, 固 gù ‘certainly’, 其 qí ‘perhaps, possibly’, and 殆 dài ‘probably’ (Meisterernst 2016a). They appear in a high position with regard to the VP, preceding the verb and other adverbials, including negative markers (Meisterernst 2016a; Wei 魏培泉 1999: 261). Root modal auxiliary verbs on the other hand usually follow negative markers and thus appear in a position below that of epistemic adverbs. In example 10a, the root modal verb 當 dāng ‘should’ expresses deontic necessity (obligation); in 10b the epistemic adverb 固 gù expresses epistemic necessity (certainty on the side of the speaker).

-

(10)

a. 我方先君後臣, 因謂王即弗用鞅, 當殺之 (Shǐjì: 68, 2227)

wǒ__fāng__xiān__jūn__hòu__chén,__yīn__wèi__wáng__jí__fú__

I__ASP__forward__ruler__put.behind__vassal,__therefore__say__king__if__

yòng__yǎng,__dāng__shā__zhī

NEG__employ__Yǎng,__DANG__kill__OBJ

I am just putting the ruler first and the vassal last, and therefore I told the king that if he did not employ you, Yang, he should kill you.

b. 今陛下創大業, 建萬世之功, 固非愚儒所知。 (Shǐjì: 6254)

jīn__bìxià__chuàng__dà__yè,__jiàn__wàn__shì__zhī__

Now__sir__begin__great__enterprise,__establish__ten.thousand__generation__GEN__

gōng,__gù__fēi__yú__rú__suǒ__zhī

merit,__GU__NEGcop__stupid__Confucian__REL__know

Now has Your Highness started a great enterprise and established merit for ten thousand generations, this is certainly not anything stupid Confucians can understand.

It has been claimed that root and epistemic verbs are subject to different syntactic constraints: root modals are control verbs, i.e. they take their subject as an argument, whereas epistemic modals are raising verbs.Footnote 35 A somewhat different approach has been followed in Hacquard (2006). She distinguishes two different modal categories according to the position of the modal and to the characteristics of the subject; these are epistemics/true deontics on the one hand and circumstantial modals on the other hand. The first appear in a higher position than the latter, i.e. “epistemics and deontics are interpreted above Tense and Aspect, while circumstantials are not”; additionally, they show differences in their orientation (Hacquard 2006: 114). According to Hacquard (2006), roots and epistemics can be differentiated by their subject-orientation (Su-O) and speaker/addressee-orientation (Sp/A-O). Epistemic modals do not report the subject’s, but the speaker’s or believer’s epistemic state, and “circumstantial modals do not deal with capacities of the speaker or the addressee” (Hacquard 2006: 125). Hacquard (2006: 25) claims that “With the epistemic reading, the time of evaluation of the modal is the speech time (now), and the epistemic state reported is that of the speaker. With the goal-oriented interpretation, the time of evaluation of the modal is the time provided by tense (then) and the circumstances reported are that of the subject:

-

(11)

Jane a dû prendre le train.

Jane must-pst-pfv take the train

Epistemic: Given my evidence now, it must be the case that Jane took the train then.

Goal-oriented: Given J.’s circumstances then, she had to take the train then.”Footnote 36

Consequently, the subject plays a crucial role for the analysis of the modal as an epistemic, true deontic (performative), or a circumstantial modal. One of the constraints on a subject of a deontic modal is that it has to be [+HUMAN] (e.g. Meisterernst 2010, 2011). Performativity can only be assumed in cases in which the individual under obligation, i.e. the agent of the verb embedded by the modal, is the addressee or another participant in the conversation (Portner 2009: 189). In this regard, performatives can act like imperatives. This also accounts for the LAC and EMC data. In LAC and EMC, circumstantial and deontic modal values are partly expressed by the same verbs in apparently identical syntactic positions. However, differences can be observed in their scope relations with regard to negation (Meisterernst 2016c); this leads to the assumption that they can also be distinguished syntactically. This has the effect that the modal verb 可(以) kě(yǐ), a circumstantial modal in its affirmative variant, occupies a position different from and lower than its negated deontic variant NEG 可(以) kě(yǐ) NEG. Epistemic modals (i.e. modal adverbs)—and the few deontic modal adverbs—operate on the level of CP (Complemetizer phrase). These facts confirm Hacquard’s hypothesis, but also the hierarchy of functional heads proposed in Cinque (1999).

In the following, only modal auxiliaries, which can express root or deontic modal values in LAC and EMC, will be discussed with particular focus on the lexical aspect of the complement they select. Of the modal verbs expressing possibility, only 可/可以 kě/kěyǐ will be included. The discussion will predominantly be based on the claims proposed in Abraham and Leiss for the relation between the system of the aspectual and the modal markers. It will be proposed that in Chinese, too, a close relation exists between the modal readings and the aspectual (aktionsart) features of the verb. According to the arguments presented in Section 2.2, it will be hypothesised that it is the lexical aspect [+/− TERMINATIVE] instead of the grammatical aspect [+/−PERFECTIVE] which provides a cue for the modal interpretation of the predicate to the effect that the root modal reading is more natural with an event complement than with an atelic complement. The increase in complexity in the modal system of MC observable in the early Medieval Buddhist literature might have been triggered by the loss of the morphological marking of the lexical aspect, similar to the Germanic languages. But this issue still requires more research. Additionally, observations with regard to the Japanese system will be taken into consideration. In Japanese, the aspect-modality link is supposed to be motivated by general cognitive principles (see Abraham and Leiss for Japanese (2008: xix): “The temporality of root modal sentences differs from epistemic modal sentences in that deontic modal sentences require “Speech act time ≠ Event time”, while there are no such restrictions on sentences with epistemic modals… the crucial factor being (not “temporal”, but) “time” referential, rather than aspectual.” According to Abraham and and Leiss in Japanese, the “grammatical aspect only provides a cue to modal interpretation” (Narrog 2008: 279), but does not determine it.

3 Root modal markers in Han period Chinese and their complements

The term root modality extends the bipartite distinction between deontic and epistemic modality and covers circumstantial modal values (conditioning external factors (Palmer 2001: 9)), root possibility, ability and volition. Deontic modality is concerned with necessary or possible acts performed by morally responsible agents (Lyons 1978: 823), usually distinguished into the subcategories obligation and permission (Meisterernst 2008b: 87). In LAC and EMC direct expressions of obligation, ‘you must, do!’ are relatively infrequent; they apparently gain more prominence in the Buddhist literature.

Deontic modal values (obligation) can be expressed indirectly with the auxiliary verb 可(以) kě(yǐ) ‘can’ in combination with double negation 不可(以)不 bù kě(yǐ) bù ‘cannot not >>> must’.Footnote 37 The only auxiliary verb expressing a direct obligation in an affirmative sentence is the auxiliary verb 必 bì ‘must’.Footnote 38 As a modal verb, it conveys deontic modality in the strict sense. Besides this, in EMC, the verb 當 dāng ‘match, correspond’ increasingly occurs as a deontic modal auxiliary verb ‘ought to, should’ (Meisterernst 2011). The strength of advice of 當 dāng is weaker than that of bì 必. The modal expressions of deontic modality typical for LAC, i.e. NEG 可/可以 kě/kěyǐ NEG and the modal auxiliary 必 bì, apparently cease to be relevant in the EMC Buddhist literature and new forms develop and increase the complexity of the modal system.

In the following section, the different modal auxiliary verbs conveying the root/deontic modal (excluding root possibility and ability) value of obligation and necessity are discussed with particular regard to the temporal and aspectual structure of the complement they select.

3.1 The modal auxiliary verb 可 kě with double negation: 不可不 bù kě bù , 不可以不 bù kě yǐ bù ‘must’ Footnote 39

The auxiliary verb kě(yǐ) 可(以) predominantly expresses circumstantial root possibility (Meisterernst 2008b), i.e. possibility due to external factors and circumstances ‘can, possible’. It thus belongs to the class of ‘first modals’ (Leiss 2008: 16). In the doubly negated construction NEG 可(以) kě(yǐ) NEG vP, it always codes strong deontic modality, i.e. a strong obligation ‘must’. In contrast to the affirmative construction with 可(以) kě(yǐ), it never expresses root possibility (Meisterernst 2008b). The obligation is conveyed in an indirect way precisely expressing ‘it is not possible that not p ¬◊¬ p’ = □p ‘it is necessary that p’; the basic meaning of 可 kĕ being ‘possible, permissible’. The subject can range from a [+/−HUMAN] theme subject to a [+HUMAN] experiencer or an agent subject. Depending on the construction, it can be the direct addressee (second person), or another participant in the speech. In LAC, a transitive or intransitive verb following 可 kě is usually passivized (or unaccusative), i.e. its internal argument appears in subject position as a theme/patient subject and the embedded verb is resultative [+TELIC/TERMINATIVE] as in example 12a from LAC and in 12b from Han Chinese. The examples in 12 have a theme subject. In all the examples, the predicate is [+TELIC/RESULTATIVE] whether overtly marked or not. This is required by the syntactic constraints of 可 kĕ.

-

(12)

a. 范、中行數有德於齊, 不可不救。 (Shǐjì: 32; 1505)

fàn,__zhōngháng__shuò__yǒu__dé__yú__qí,__bù__kě__bù__jiù

Fan,__Zhonghang__often__have__favour__PREP__Qi,__NEG__can__NEG__rescue

The Fan and Zhonghang families have often done favours to Qi, they have to (< cannot not) be rescued.

b. 范、中行數有德於齊, 不可不救。 (Shǐjì: 32; 1505)

fàn,__zhōngháng__shuò__yǒu__dé__yú__qí,__bù__kě__bù__jiù

Fan,__Zhonghang__often__have__favour__PREP__Qi,__NEG__can__NEG__rescue

The Fan and Zhonghang families have often done favours to Qi, they have to (< cannot not) be rescued.

In order to neutralize the passivization effect, the insertion of 以 yǐ is required as in the examples in 13 from LAC and Han Chinese, respectively.Footnote 40 The modal predicates are usually either future-projectingFootnote 41 or generic as in example 13a. Generic readings can appear as a subclass of deontic readings (Leiss 2008: 23).Footnote 42 In the examples in 13, the subject is agentive and accordingly [+HUMAN]; in 13b, the speaker puts a direct obligation on the addressee subject. The verbs in the complements of the modal all include an event argument.

-

(13)

a. 君子不可以不刳心焉。 (Zhuāngzǐ 12.2.1)

jūnzǐ__bù__kě__yǐ__bù__kū__xīn__yán

Gentleman__NEG__can__YI__NEG__cut.open__heart__PP

A gentleman must (< cannot not) cut open his heart at it.

b. 大將軍尊重益貴, 君不可以不拜. (Shĭjì: 120; 3108)

dà__jiàngjūn__zūn__zhòng__yì__guì,__jūn__bù__kĕ__yĭ__bù__bài

great__general__venerable__important__more__honour,__prince__NEG__can__YI

NEG__bow

The great general is very important and is receiving more and more honours; you have to (< cannot not) bow to show him your reverence.

Although a deontic modal marker is supposed to select a telic complement, some of the verbs are not genuinely telic. The verbs in 14 are atelic state verbs (including adjectives); in this construction, they have to add an event variable, i.e. they have to add a [+TELIC] feature to be licenced as a complement of 不可(以)不 bùkĕ(yǐ)bù.Footnote 43 In examples 14a and 14b, the subject is a [−HUMAN] theme subject; in example 14c with 可以 kěyǐ, the subject is an experiencer subject. As a state verb, 知 zhī in 14d functions as a stage-level predicate; these display constraints similar to event verbs in Chinese.

-

(14)

a. 君子曰:「位其不可不慎也乎! (Zuŏzhuàn, 成公二年 Chéng 2)

jūnzǐ__yuē:__wèi__qí__bù__kě__bù__shèn__yě__hū

gentleman__say__positiontheme__MOD__NEG__can__NEG__careful__SFP__SFP

The gentleman says: “The rank has to be (< cannot not be) treated carefully!”

b. 親而不可不廣者, 仁也; (Zhuāngzǐ 11.5.10)

qīn__ér__bù__kě__bù__guǎng__zhě,__rén__yě

intimate__CON__NEG__can__NEG__broaden__RELsubj_theme,__benevolence__SFP

What is intimate but has to (< cannot not) be broadened, this is benevolence.

c. 齊將伐晉, 不可以不懼。」(Zuǒzhuàn, 襄公二十二年 Xiāng 22)

qí__jiāng__fá__jìn,__bù__kě__yǐ__bù__jù

Qi__FUT__attack__Jin,__NEG__can__YI__NEG__fear

Qi will attack Jin, we have to (cannot not) be(come) afraid.

d. 故有國者不可以不知春秋, (Shĭjì: 130; 3298)

gù__yŏu__guó__zhĕ__bù__kĕ__yĭ__bù__zhī__chūnqiū

therefore__have__state__NOM__NEG__can__YI__NEG__know__spring-autumn

Therefore, those who have a state/are responsible for a state must know the Spring and Autumn Annals …

In example 14d both, a deontic, future-projecting reading in a strict sense and a generic reading are possible. The deontic reading refers to the particular requirement of individualized situations in the future and the generic reading to general rules and regulations. According to Ziegeler (2008: 55), ‘potentiality’ is the ‘common semantic denominator’ of normative generic expressions and deontic modality.

In the doubly negated construction, 可/可以 kě/kěyǐ always expresses deontic modality with a strong speaker orientation. Different from the other modal auxiliary verbs discussed here, the complement of 可 kě requires different analyses depending on the presence of the functional head 以 yǐ. These are as follows:

-

a)

可 kĕ + vP: a passivized resultant state complement, the focus is on the patient or theme of the event and on the change of state point tm; the role of the causer (agent) of the event is not included and

-

b)

可以 kěyǐ + vP: an event predicate with an agent (causer) subject, or a state predicate referring to a genuine state (e.g. with adjectives or state verbs) and an experiencer subject.Footnote 44 Only state verbs which can include an event variable are available for this construction.

Thus, 可 kě requires a patient/theme subject and a resultative complement on a regular basis. In both constructions, most of the complements selected refer to events or to states resulting from a previous event either in their transitive or their passivized (or unaccusative) forms. The complement can refer either to E1 (including tm) or to E2 (including tm) with verbs which have the structure proposed for event (terminative) verbs in Abraham and Leiss (2008: xiii). Temporally, they all have the characteristic: S ≠ E (speech time is not identical with, i.e. it precedes event time),Footnote 45 the structure proposed for deontic modality in Japanese by Narrog (2008), the general structure for deontic modality which typically refers to an obligation performed in the future.

(15)

With a passivized complement, the modal is exclusively speaker oriented and with an agentive complement, it is speaker–addressee oriented; this argues for its analysis as a true deontic modal according to Hacquard (2006).

3.2 The modal verb 當 dāng

The modal function of 當 dāng grammaticalizes from a verb with the basic meaning ‘match, correspond’.Footnote 46 As a modal auxiliary verb, it expresses root necessity: □p ‘it is necessary that p’, roughly corresponding to the modal should in English. In this function, it is regularly attested from the Han period on.Footnote 47 Although it can be employed in true performative deontics, it predominantly appears in indirect suggestions; the agent is frequently unspecified. The verb in its complement is mostly a telic agentive verb in transitive or derived, i.e. passivized/resultative constructions; the obligation is based on laws, rules and norms. Contrary to the strong deontic construction NEG 可(以) kě(yǐ) NEG vP and to the modal auxiliary verb 必 bì, the speaker does not necessarily expect compliance on the side of the frequently only implied agent. As with should in English, the modal force of obligation is weaker than with must. The strength of obligation is induced by the strength of the ordering source for the modal. With strict laws, these ordering sources imply a stronger obligation than with what is, e.g. predetermined by destiny (Meisterernst 2011, 2012). Epistemic values are confined to 當 dāng in the complement of an epistemic, an attitude verb, and do not depend on the modal. After the Han period, the employment of 當 dāng changes, and in the Buddhist literature, 當 dāng tends to express more direct obligations, i.e. performatives. These are frequently characterized by a second or third person subject referring to the addressee and the specified agent of the required action; in these cases, the speaker and the agent of the requested action are not identical.

In the examples in 16, an event verb appears in a passive construction with a theme subject. Although the structure is similar to that of 可 kě with a passive complement, the passive reading is not required syntactically, but depends on the role of the subject. The modal predicate is future-projecting and the complement of 當 dāng refers to a resultant state and to the process leading up to it, i.e. it is [+TELIC]. But at this period, any morphological marking of the resultant state was certainly no longer transparent for the speaker.Footnote 48 Although these examples evidently represent cases of deontic modality, the identification of a particular agent is explicitly avoided. This employment is most typical for 當 dāng in Han Chinese.

-

(16)

a. 群臣議, 皆曰「長當棄市」。 (Shǐjì: 10; 426)

qún__chén__yì,__jiē__yuē__Cháng__dāng__qì__shì

All__minister__discuss,__all__say__Chang__DANG__abandon__expose-marketplace

The ministers discussed, and they all said: “Chang should be executed and exposed on the marketplace.”

b. 軍法期而後至者云何? 對曰:「當斬。」 (Shǐjì: 64; 2158)

jūn__fǎ__qí__ér__hòu__zhì__zhě__yúnhé?__

Military__law__stipulated.time__CON__later__arrive__NOM__what-about?__

duì__yuē:__dāng__zhǎn

answer__say:__DANG__behead

“According to the military law: someone who arrives later than the appointed time, what happens [to him]?” He answered: “He should be beheaded.”

The examples in 17 are both transitive and agentive; the agent of the verb is identical to the addressee of the obligation. Example 17a represents one of the less frequent cases in Han period Chinese in which a direct, though polite command, is issued by 當 dāng. In example 17b, the reference time is located in the past and precedes the speech time, and two different times are involved in the modal predicate.Footnote 49 Nevertheless, the modal is still future-projecting.Footnote 50

-

(17)

a. 王當歃血而定從, (Shǐjì: 76; 2368)

wáng__dāng__shà__xuè__ér__dìng__zōng,__

King__DANG__smear__blood__CON__establish__alliance,_

Your majesty should smear blood [on his lips] in order to establish alliance …

b. 我方先君後臣, 因謂王即弗用鞅, 當殺之. (Shǐjì: 68; 2227)

wŏ__fāng__xiān__jūn__hòu__chén,__yīn__wèi__wáng__jí__

I__ASP__forward__ruler__put.behind__vassal,__therefore__say__king__if__

fú__yòng__Yăng,__dāng__shā__zhī

NEG__employ__Yang,__DANG__kill__OBJ

I am just putting the ruler first and the vassal last, and therefore I told the king that if he did not employ you, Yang, he should kill you.

The example in 18 has [−HUMAN] experiencer subjects; the verbs are intransitive. The verbs in the first clause 衰 shuāi ‘decline’, and 亂 luàn ‘(cause to) be in disorder’ can be both atelic or telic. The verb 治 chí/zhì ‘put in order, govern’, ‘well-governed, in good order’ (see ex. 7) belongs to the verbs for which an aspectual morphology has been reconstructed. The semantic features of the subject are in general assumed to be more typical for epistemic than for deontic readings, but all complements include an event variable and refer to resultant states which are [+TELIC]. Thus, they do not differ significantly from some of the examples discussed above. The modal is future-projecting.

-

(18)

國當衰亂, 賢聖不能盛; 時當治, 惡人不能亂。 (論衡 lùnhéng ‘On Balance’: 53.5.26)

guó__dāng__shuāi__luàn,__xián__shèng__bù__néng__chéng;__shí__

State__DANG__decline__chaos,__virtuous__wise__NEG__can__hold;__time__

dāng__zhì,__è__rén__bù__néng__luàn

DANG__well.governed,__bad__man__NEG__can__chaos

If a state is supposed to have declined and to be in chaos, even virtuous and wise people cannot keep it in order; if the time is supposed to be well-governed, even bad people cannot cause chaos.

All instances of 當 dāng presented above are future-projecting; the obligation imposed can refer to an agentive event, but also to a future resultant state and the process leading up to it without any agency involved. The latter instances are similar to those with 可 kě with a passivized (unaccusative) resultative complement. In past tense contexts, 當 dāng obtains a counterfactual reading.Footnote 51 According to Sparvoli (2015), a counterfactual reading in the past is the typical actuality entailment for deontic modals and one of the possible readings (besides an epistemic reading) in past contexts. The past context can, but does not have to be explicitly marked. In example 19a, the event preceding the modal predicate is marked as completed by the aspectual adverb 已 yǐ; in 19b, the event is located in the past by the adverbial 先 xiān ‘earlier’ in the complement of 當 dāng.

The modal predicate is always future-projecting, although the prospective event is located in the past. The speaker refers to a reference time preceding speech time which serves as the point of reference for the projected future situation time. The counter-factual effect in past tense contexts is produced when both reference time and situation time precede speech time.

-

(19)

a. 項羽已救趙, 當還報, 而擅劫諸侯兵入關, 罪三。 (Shǐjì: 8; 376)

xiàng__yǔ__yǐ__jiù__zhào,__dāng__huán__bào,__ér__shàn__

Xiang__Yu__already__rescue__Zhao,__DANG__return__report,__CON__usurp__jié__zhūhóu__bīng__rù__guan,__zuì__sān

force__feudal-lord__soldier__enter__pass,__guilt__three

Xiang Yu had already rescued Zhao and should have returned and reported, but he forced the troops of the feudal lords on his own authority to enter the pass, this was his third offence.

b. 「吾當先斬以聞, 乃先請, 為兒所賣, 固誤。」 (Shǐjì: 101; 2746)

wú__dāng__xiān__zhǎn__yǐ__wén,__nǎi__xiān__qǐng,__

I__DANG__first__decapitate__CON__let-hear,__then__first__ask,__

wéi__ér__suǒ__mài,__gù__wù

PASS__boy__PASS__sell,__certainly__mistake

I should have decapitated him first and then told; so, when I asked first, I was deceived by the boy, this was certainly a mistake.

The verbs in the complement of 當 dāng usually refer to events, i.e. they are telic and accordingly compatible with the perfective aspect. Originally atelic have to include an event variable in their temporal structure, when they appear in the complement of 當 dāng. In the Han period literature, the supposed agent of the event, the addressee of the obligation, is frequently not focused on. Two different variations are possible:

-

a)

The complement verb appears either in an unaccusative (passive) construction referring to a resultant state similar to the construction with 可 kě: the agent is irrelevant.

-

b)

It appears in an agentive/causative construction in which the subject of the agentive verb does not appear explicitly.

The temporal structure of the complement of 當 dāng resembles that of 可/以) kě(yǐ) (E ≠ S). Even if the modal itself is located in the past, i.e. it precedes speech time, the complement is still future-projecting, i.e. it follows reference time and speech time: S,R_E.

(20)

Identical to 可 kě, the modal is exclusively speaker oriented with an unaccusative or passivized complement. With an agentive complement, it is speaker–addressee oriented, this argues for its analysis as a true deontic modal according to Hacquard (2006).

3.3 The modal 必 bì expressing deontic and epistemic modality

The modal 必 bì differs considerably from the modal verbs discussed above both semantically and syntactically. 必 bì in LAC and EMC is generally regarded as expressing ‘certainty, necessity’, usually corresponding to English ‘must’ and the like if verbal, and to modal adverbs such as ‘certainly, necessarily’ if adverbial. For Han Chinese, a functional split between deontic and epistemic 必 bì has been proposed (Meisterernst 2013). With a deontic reading, 必 bì has to be analysed as a modal auxiliary verb ‘must/need’; with an epistemic reading, expressing confidence on the side of the speaker, it has to be analysed as a modal adverb ‘certainly’ (Meisterernst 2010, 2013). Since it predominantly refers to future contexts, the analysis of epistemic 必 bì as a modal adverb and not as a modal verb is semantically more conclusive. Future reference is according to, e.g. Coates (1983) and Bybee et al. (1994) usually not available for modal auxiliary verbs such as English MUST in their epistemic reading, whereas it is the default reference with deontic modals.Footnote 52 Additionally, the modal auxiliary verb and the modal adverb 必 bì apparently occupy different positions with regard to the VP. The modal adverb operates on the level of CP above aspect and negation, the position typical for epistemic markers, whereas the modal auxiliary verb 必 bì appears below negation (Meisterernst 2013) (and below aspect). This is the default position of root (circumstantial) modal auxiliary verbs in LAC and Han Chinese; they constitute a vP of their own which selects a non-finite TP as its complement (Meisterernst 2015b). This is in accordance with (Hacquard 2006), who assumes that the position of circumstantial modals is different from that of true deontic and of epistemic verbs. The latter pattern together because true deontics, in contrast to circumstantial modals, are speaker oriented and not subject oriented: they put an obligation on the addressee. According to Hacquard’s hypothesis (Hacquard 2006: 122), the deontic modals discussed in this paper are supposed to appear in a position above aspect: i.e. deontic NEG 可(以) kě(yǐ) NEG should appear in a higher position than circumstantial 可(以) kě(yǐ).Footnote 53 Another argument for a functional split of 必 bì into a (deontic) modal verb and an (epistemic) adverb can be deduced from Abraham and Leiss (2009) who argues against the frequent semantic equation of modal verbs and modal adverbials in the literature in examples such as the following (see also Meisterernst 2016a):

-

(21)

a. Er__muss__die__Klausur__bestanden__haben__(modal verb)

3SG__MUST__DET__test__passed__have

He must have passed the test.

b. Er__hat__die__Klausur__sicherlich__bestanden__(modal adverb)

3SG__has__DET__test__certainly__passed

He certainly passed the text. (Abraham and Leiss 2009: 8)

Abraham and Leiss (2009) claim that the category source is the distinctive feature of epistemic verbs and epistemic adverbs. Epistemic marking by adverbs does not include a source of information for the epistemic evaluation of the speaker: epistemic adverbs are monodeictic, while epistemic verbs are bi-deictic (Abraham and Leiss 2009: 13) including both the speaker evaluation and the source. The fact that only the speaker evaluation is included in epistemic adverbs can also argue for their availability for expressing future reference, contrary to epistemic verbs.

Although 必 bì seems to be the only direct marker of strict deontic modality in LAC and Han Chinese, the function as an epistemic modal adverb expressing (mostly) future certainty is evidently its predominant function from the earliest instances on. This function of 必 bì can be accounted for by what Coates labels ‘pure logical necessity’, expressing confidence in a logical necessity on the side of the speaker. To obtain a deontic reading of 必 bì, a causative/agentive subject is a necessary condition. This is evidenced by the contrastive examples in 22a and 22b, which contain the verb 立 lì ‘set up, establish’, a default [+TELIC] verb. In example 22a with a non-overt causative/agentive addressee subject, 必 bì has a deontic reading, conveying a direct obligation to the addressee. In 22b with a theme subject, it is epistemic referring to the speaker’s commitment to a future necessity. The verb in 22b has a passive reading. Although a passive reading of the complement is quite natural with the root modal auxiliaries 可以 kě(yǐ) and 當 dāng, this is not the case with deontic 必 bì which requires an agent or a causer subject for a deontic reading.

Deontic:

-

(22)

a. 麇曰:「必立伯也, 是良材。」 (Zuŏzhuàn, 哀公十七年 Āi 17)

jūn__yuē__bì__lì__bó__yĕ,__shì__liáng__cái

Jun__say:__BI__enthrone__Bo__SFP,__this__good__talent

Jun said: “You must enthrone Bo, he is a talented man.”

Epistemic:

-

b.

曰:「余夢美,必立。」 (Zuŏzhuàn, 哀公二十六年 Āi 26)

yuē__yú__mèng__mĕi,__bì__lì

Say:__I__dream__beautiful,__BI__enthrone

My dream was beautiful, I will certainly be enthroned.

Although an agentive subject is a necessary condition for the deontic reading, a non-agentive subject is not a necessary condition for an epistemic reading. Both 22c and 22d contain a causative/agentive subject and the [+TELIC] verb 救 jiù ‘rescue’, but 22d has an epistemic reading. The subject of the modal predicate is a third person [+/−HUMAN] subject which renders a deontic interpretation less likely.Footnote 54

Deontic:

-

c.

由不然, 利其祿, 必救其患。 (Shǐjì 37; 1601)

yóu__bù__rán,__lì__qí__lù,__bì__jiù__qí__huàn

you__NEG__be.like,__profit__his__salary,__BI__save__his__trouble

I, You, am not like that, I profit from his salary, and so I must save him from his trouble.

Epistemic:

-

d.

若伐曹,衛,楚必救之,則宋免矣。 (Shǐjì 39; 1664)

ruò__fá__cáo,__wèi,__chǔ__bì__jiù__zhī,__zé__sòng__miǎn__yǐ

if__attack__Cao,__Wei,__Chu__BI__save__OBJ,__then__Song__escape__SFP

If we will attack Cao and Wei, Chu will certainly help them, and then Song will escape.

3.3.1 Typical instances of 必 bì as a modal auxiliary verb: Deontic reading

The examples in 23 represent default cases of deontic modality expressed by 必 bì. The verbs are typical [+TELIC] verbs with an agent (causer) subject; in 23b, the verb 存 cún which can have an atelic reading ‘exist, remain, survive’, appears in its causative telic reading ‘make-exist = preserve’. The predicates are future-projecting. Example 23a represents deontic modality in its strictest, i.e. in the performative sense; a direct command is issued from a speaker to an addressee. These modals require a [+HUMAN] agentive subject and an event verb as the complement of the modal. In example 23b and 23c, the subject is a first or a third person subject, respectively. The speaker who is identical with the addressee and agent of the modal situation expresses an obligation he himself is under in 23b, and in 23c, the speaker reports an obligation on a third person.Footnote 55

-

(23)

a. 君必殺之 (國語 guóyŭ 晉語八 Jìn 8)

jūn__bì__shā__zhī

Prince__BI__kill__OBJ

You must kill him!

-

b.

「我必覆楚。」包胥曰:「我必存之。」 (Shĭjì: 66; 2176)

wŏ__bì__fù__chŭ__bāoxū__yuē__wŏ__bì__cún__zhī

I__BI__overthrow__Chu.__Baoxu__say__I__BI__preserve__OBJ

“I must overthrow Chu.” Baoxu said: “I must preserve it.”

-

c

彼見秦阻之難犯也, 必退師。 (Shĭjì: 6; 277)

bĭ__jiàn__qín__zŭ__zhī__nán__fàn,__bì__tuì__shī

That__see__Qin__obstruct__GEN__difficult__transgress,__BI__withdraw__army

When they saw that the obstructions of Qin were hard to overcome, they had to withdraw their army.

Example 24 with the verb of cognition 思 sī ‘think, think of, long for’ is more ambiguous than the preceding examples. State verbs such as 思 sī can licence an event argument and can thus appear in root modal predications; accordingly, the lexical aspect of 思 sī does not necessarily argue against a deontic reading. With deontic 必 bì, a direct command is issued to an addressee; but in 24, the obligation rather refers to the event represented by 免 miǎn ‘avoid’ than to the state of thinking represented by sī 思.Footnote 56 But in this example, an adverbial analysis of 必 bì expressing the confidence of the speaker that the proposition will be true under the conditions specified in the protasis cannot be excluded. The semantics of the verb and the experiencer subject provide some evidence in support of the epistemic analysis, since—contrastingly to kě(yǐ) and 當 dāng—deontic 必 bì by default has an agent or a causer subject. In any event, the modal predicate is future-projecting. Ambiguous cases like these probably caused the replacement of 必 bì as a modal verb in EMC.

-

(24)

吾子直, 必思自免於難。 (Shǐjì 31; 1459)

wú__zǐ__zhí,__bì__sī__zì__miǎn__yú__nàn

I__son__upright,__BI__consider__self__avoid__PREP__difficulty

My lord, you are upright, and you must consider avoiding difficulties (root)./Since my lord is upright, you will certainly consider avoiding difficulties.(epistemic)

3.3.2 Typical instances of the epistemic adverb 必 bì (modal adverb)

The epistemic modal 必 bì is predominantly attested in future-projecting contexts in matrix clauses; it most typically occurs in the apodosis of a conditional or concessive sentence.Footnote 57 The fact that epistemic 必 bì is mostly future-projecting argues against a polysemic modal auxiliary verb 必 bì comparable to the English must expressing both deontic and epistemic values. Future readings are in general not available for the epistemic reading of these verbs (e.g. Coates 1983; Meisterernst 2010; Palmer 2001; Ziegeler 2008). But they are not blocked from epistemic adverbs expressing certainty. According to Nuyts (2001: 77), the appearance of a modal in the apodosis of a conditional sentence argues particularly for an adverbial analysis, expressing “the speaker’s present evaluation (performatively)” of the probability that a particular state of affairs will come about under the conditions given in the protasis (ibid). This definition evidently supports an analysis of 必 bì as a modal adverb ‘certainly’ in most of the cases presented below. In future contexts, the speaker does not relate his commitment to the truth of his deductions from known facts; this would be the default function of an epistemic auxiliary verb. He rather conveys his confidence that under certain conditions (which are not yet true in the real world), his deductions will be true, i.e. “that a certain hypothetical state of affairs under consideration … will occur” (Nuyts 2001: 21). With an epistemic adverb, no source for the commitment is involved (Abraham and Leiss 2009). Epistemic adverbs appear very high in the syntactic structure. They take an entire proposition as their complement; consequently, they are less confined in their selectional restrictions (see Meisterernst 2016a).

The verb 喜 xǐ in example 25 is a genuine state verb; it does not combine with a perfective adverb in LAC and EMC.Footnote 58 Genuine state verbs support an epistemic reading with modal auxiliaries. Additionally, genuine intransitive state verbs do not have an agent or causer subject. The example does not refer to an obligation in the real world, but is assumed to be true by the speaker under the conditions specified in the conditional protasis. All of these argue for an analysis of 必 bì as an epistemic adverb.

-

(25)

今王事秦, 秦王必喜, 趙不敢妄動。 (Shĭjì: 70; 2298)

jīn__wáng__shì__qín,__qín__wáng__bì__xĭ,__zhào__bù__găn__wàng__dòng

Now__king__serve__Qin,__Qin__king__BI__happy,__Zhao__NEG__dare__rash-move

If you now serve Qin, the King of Qin will certainly be happy, and Zhao will not dare to move rashly.

In example 26, future certainty regarding the occurrence of an adverse situation is expressed. The fact that the subject is a [−HUMAN] theme argues against a deontic reading of the modal despite the [+TELIC] verb.

-

(26)

齊秦合則患必至矣。 (Shĭjì: 70; 2287)

qí__qín__hé__zé__huàn__bì__zhì__yĭ

Qi__Qin__join__then__trouble__BI__arrive__SFP

If Qi and Qin ally, then trouble will certainly arrive.

In the examples in 27, nothing argues against a deontic interpretation on a par with example 23b with a first person agentive subject. All verbs are event verbs. Time span adverbials as in example 27a do not provide an argument against a deontic interpretation, since they combine with events identical to deontic modal auxiliary verbs. In this example, the speaker conveys his confidence as a supporting argument for the performative acts, whereas in 27b he conveys his confidence in the occurrence of a future event according to the conditions related in the respective protases. All propositions are future-projecting.

-

(27)

a. 慎勿與戰, 毋令得東而已。我十五日必誅彭越, 定梁地, 復從將軍。(Shĭjì: 7; 329)

shèn__wù__yǔ__zhàn,__wú__líng__dé__dōng__ér__yǐ.__wŏ__shí__

careful__NEGmod__give__battle,__NEGmod__order__get__east__CON__finish__I__ten_

wŭ__rì__bì__zhū__péng__yuè,__dìng__liáng__dì,__fù__cóng__jiàngjūn

five__day__BI__execute__Peng__Yue,__settle__Liang__territory,__again__follow__general

Be careful not to join them in fight; just do not order them to get [to] the east. I will certainly execute Peng Yue, pacify the territory of Liang and join you, general, again within fifteen days.

b. 不勝, 則我引兵鼓行而西, 必舉秦矣。 (Shǐjì 7; 305)

bù__shèng,__zé__wǒ__yǐn__bīng__gǔ__xíng__ér__xī,__bì__jǔ__qín__yǐ

NEG__win,__then__I__lead__army__drum__march__CON__west,__BI__conquer__Q in__SFP

If it (Qin) does not win, then we will lead our troops and, following the beating drums, we will march west, and we will certainly conquer Qin.

Examples such as 27, display characteristics typical for deontic modal interpretations, i.e. the modal modifies event predicates with telic verbs with [+HUMAN] agent or causer subjects. Nevertheless, in the examples presented, bì evidently expresses epistemic, and not deontic modality, referring to a certainty on the side of the speaker with regard to the occurrence of a future event, frequently under conditions specified in a conditional protasis. In this regard, they show the same orientation, i.e. a speaker orientation as true deontics do according to Hacquard (2006: 114): the latter display a speaker/addressee–orientation (Sp/A-O). Since modal 必 bì also expresses deontic modality, the speaker orientation of propositions with 必 bì seems to be the semantic link between the deontic and the epistemic functions.

The examples show that no selectional restrictions with regard to the lexical aspect of the verb in the complement of epistemic 必 bì exist. In both the deontic and the epistemic reading of 必 bì, the modal predicate is predominantly future-projecting. Additionally, both readings of 必 bì are speaker oriented; they apparently differ in the fact that deontic 必 bì has a strong addressee additional to the speaker orientation. The agent orientation of 必 bì is much stronger than that of the root and circumstantial modal auxiliary verbs 當 dāng and 可 kě; these are frequently explicitly not directed to a specified addressee. Consequently, in the absence of syntactic devices, it is the syntacto-semantic features of the subject which are relevant for a distinction between the verbal and adverbial function of 必 bì: the deontic reading is confined to an addressee subject that functions as an agent or causer. The epistemic function is not constrained with regard to its subject. Due to the particular semantics of 必 bì as a marker of deontic modality with a strong agent orientation, the temporal structure of the complement of deontic bì 必 differs from that of the root modal auxiliary verbs 可(以) kě(yǐ) and 當 dāng. The verbs in the complement of 必 bì are never passivized and do never refer to a resultant state as they do with 可(以) kě(yǐ) and 當 dāng. They can only refer to E1 and its final point tm, but not to the resultant state E2.

(28)

In its epistemic reading, 必 bì is not confined to this temporal structure, and the temporal part E2, the (resultant) state part, can also be included in the complement of 必 bì; this is another distinctive feature of the two modal readings. As an epistemic adverb, 必 bì can to a certain extent be compared to the other epistemic markers of Han period Chinese. These—together with some other adverbs expressing factivity and other modal values—appear very high in the hierarchy of adjuncts and they take an entire proposition as their complement (Meisterernst 2016a; Wei 魏培泉 1999). Evidently, epistemic adverbs are not subject to the same constraints with regard to the lexical aspect of their complement as modal auxiliary verbs; they operate on a different syntactic level. Accordingly, they do not provide any counter-evidence to the hypothesis proposed by Abraham and Leiss (2008).

3.3.3 Modal 必 bì and negation: 不必 bùbì

It has been demonstrated that although the modals NEG 可(以) kě(yǐ) NEG and 必 bì seem to have similar modal functions, they display considerable structural differences. These differences become additionally apparent when 必 bì is negated. Although Lü (1942, 2002: 255) claimed that 不可(以)不 bù kě(yǐ) bù and 必 bì are semantically identical, he is also one of the first to account for the differences in modal notions in combination with negation; the latter can, e.g. serve to distinguish between deontic and anankastic modality.Footnote 59 A distinction on these lines has already been proposed by Gao Mingkai (Gao 高名凯 1948, 2001) with the two modal notions 應然 yìngrán ‘duty’ and 必然 bìrán ‘necessity’ (Gao 2001) corresponding to deontic and anankastic modality. The distinction between the two is most clearly revealed in the negative form.

-

(29)

a. Deontic prohibition

‘it is necessary that not p = it is not possible that p: □¬p = ¬◊ p’

b. Anankastic exemption

‘it is not necessary that p = it is possible that not p: ¬□p = ◊¬p’ (Sparvoli 2015)

This is exemplified by the following examples from Modern Mandarin:

-

(30)

a. 他不應該去台北

tā__bù__yīnggāi__qù__tàiběi

He__NEG__must__go__Taibei

He must not go to Taibei.

b. 他不必去台北

tā__bù__bì__qù__tàiběi

He__NEG__necessary__go__Taibei

He does not have to go to Taibei. (Sparvoli 2015)

In this example, the negated form of 必 bì demonstrates that it rather expresses anankastic than deontic modality. Anankastic modality is defined by von Wright as “A statement to the effect that something is (or is not) a necessary condition of something else…” (von Wright 1963: 10, cf. Sparvoli 2015). A typical example would be as follows

-

(31)

‘If the house is to be made habitable, it ought to be heated.’ (von Wright 1963: 9, note 10, cf. Sparvoli 2015).

Although the examples in Section 3.3.1 do not correspond exactly to von Wright’s example, they frequently express a practical necessity according to circumstances. This is particularly evident in example 23c repeated here as 32.

-

(32)

彼見秦阻之難犯也, 必退師。 (Shĭjì: 6; 277)

bĭ__jiàn__qín__zŭ__zhī__nán__fàn,__bì__tuì__shī

That__see__Qin__obstruct__SUB__difficult__transgress,__BI__withdraw__army

When they saw that the obstructions of Qin were hard to overcome, they had to withdraw their army.

As Sparvoli points out, deontic and anankastic modals are interchangeable in the affirmative form, but they are not when they are negated. The following example demonstrates the difference between 不可以不 bùkěyǐbù and 不必 bùbì, and it argues strongly for an analysis of 必 bì as an anankastic modal in contrast to 不可以不 bùkěyǐbù which is deontic. For a comparison, see example 33a.

-

(33)

a. 四鄰諸侯之相與, 不可以不相接也,然而不必相親也, (Xúnzǐ 12.10.6)

sì__lín__zhūhóu__zhī__xiāng__yŭ,__bù__kě__yǐ__bù

Four__neighbour__feudal__lord__GEN__mutual__be__close,__NEG__can__YI__NEG__xiāng__jiē__yě,__ránér__bù__bì__xiāng__qīn__yě

mutual__connect__SPF,__but__NEG__BI__mutual__close__SFP

Regarding the relation between [the ruler and] the feudal lords from the four neighbouring directions, they must be mutually connected, but they do not have to be close to each other.

The predicate with 不可以不 bùkĕyǐbù expresses an obligation according to norms and rules; they negative variant of ‘must be mutually connected’ would be ‘must not/may not be mutually connected’, a prohibition as in 33b.Footnote 60

-

a)

臣聞敗軍之將,不可以言勇,亡國之大夫, 不可以圖存. (Shĭjì: 92; 2617)

chén__wén__bài__jūn__zhī__jiàng,__yán__yŏng,__

subject__hear__defeat__army__SUB__general,__NEG__can__YI__speak__bravery,

wáng__guó__zhī__dàifū,__bù__kĕ__yĭ__tú__cún

perish__land__GEN__dignitary,__NEG__can__YI__plan__exist

I have heard that the general of a defeated army may not speak about bravery and the dignitaries of a perished country may not devise plans for maintenance.

These structural differences provide a further argument for a syntactic and semantic distinction of the modal 必 bì from the deontic modals 不可(以)不 bùkĕ(yǐ)bù and 當 dāng. In Meisterernst (2016c), in a study on the scope of negation with deontic modal verbs and predicates, it has been demonstrated that modal bì appears indeed in a position within the lexical layer and lower than the modals bùkĕ(yǐ)bù and dāng; the latter appear in the layer between epistemic and circumstantial modals in the cartography of modal verbs (see Tsai 2015).

4 Conclusions

The preceding discussion demonstrates that root/deontic modal auxiliaries take event (telic) verbs or verbs that can add an event argument to their temporal structure as their complement; they are all future-projecting, i.e. as in Japanese, they all have the temporal structure S ≠ E (speech time is not identical with, i.e. it precedes event time), even if the modal is located in the past. With regard to the temporal structure of the complement, two different groups of root modal auxiliary verbs can be distinguished. The first group, represented by the modals NEG kě(yǐ) NEG and 當 dāng, allows both the process part E1 leading up to a change of state point tm and the resultant state part E2 in their temporal structure.

(34)